Catch up on the background of Cop City with our earlier coverage.

Organizers in the movement against Cop City — the controversial proposed police training center in Atlanta that is estimated to cost $100 million, clear cut large swaths of forest, and disrupt Black communities surrounding it — are in the midst of a nationwide tour, speaking in more than seventy cities to educate the public and encourage participation in a demonstration planned for November 10-13 in Atlanta.

Dubbed Block Cop City, the aim is a mass nonviolent direct action in Weelaunee Forest to halt Cop City’s construction.

Touring across the Northeast, organizer Jamie Peck spoke at Democracy Creative on Pine Street in Burlington last Thursday at an event co-sponsored by the Peace & Justice Center. She explained Cop City, the state of the grassroots movement against it, and what needs to be done next.

To the extent that the movement has garnered headlines over the past summer, it’s been largely coverage of a ballot measure activists are hoping to present to Atlantans that would allow residents to finally decide whether Cop City will move forward. Despite gathering more than double the 50,000-signature requirement for placement on the ballot, Atlanta officials are raising procedural and legal hurdles to keep the measure from even appearing before voters. Originally slated for the November elections, as of now the measure will likely be placed on the next scheduled election day: March 12, 2024, primary day.

If and when the voters of Atlanta get their say, Peck is confident in the outcome. “We’re very confident that it will go our way. The people of Atlanta are very much opposed to this project. And the city has dug itself in so hard at this point, it’s going to war with its own population.” She also noted that the number of signatures they collected, roughly 120,000, was far and above the total votes for all candidates in Atlanta’s most recent mayoral election, which elected Andre Dickens, a staunch proponent of Cop City.

But the ballot box isn’t the first or even primary tactic in the movement’s toolbox. Peck said that one of the movement’s strengths is its diversity of tactics: “It has not created a central organization that makes decisions and controls [what] you can do or say, it has not denounced any groups, tactics or political beliefs.” This has allowed a flourishing of methods of resistance and entry points for people across the political spectrum who want to get involved: everything from door knocking and phone banking to civil disobedience and blockades. Because of the laser focus on a common goal — stopping Cop City — much of the left infighting that plagued strategic questions of tactics hasn’t materialized, at least not in a way that has impacted the work. “I think it helps to have a very popular goal,” Peck said. “When we don’t have that, that’s when the circular firing squad happens.”

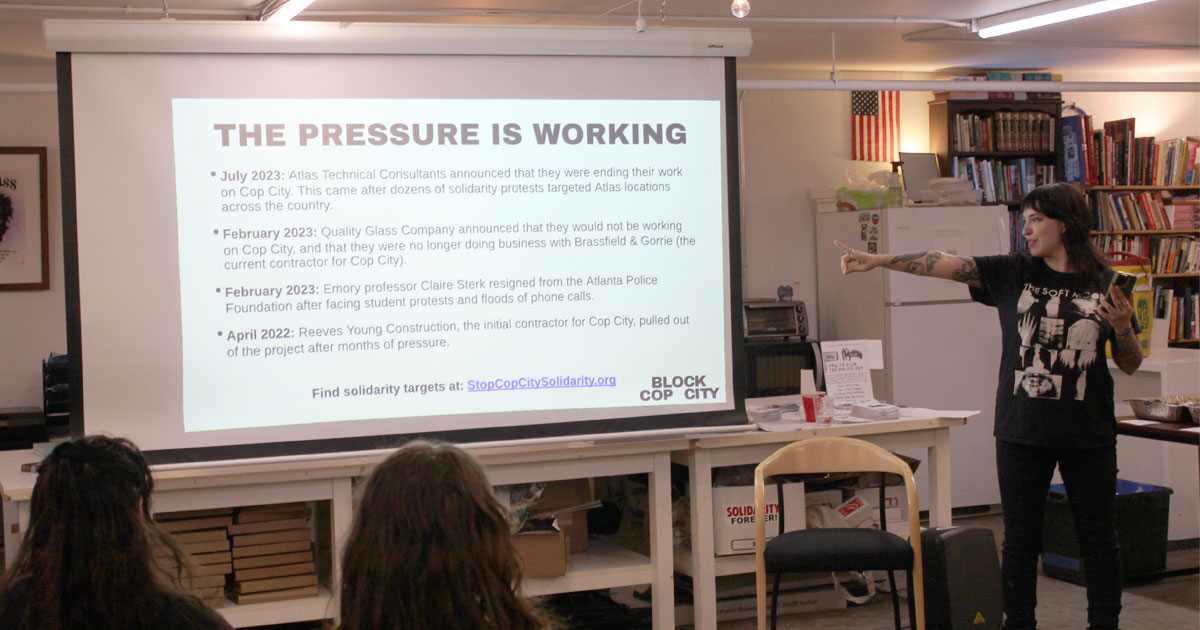

One method that has been achieving results is undermining Cop City by going after the organizations and people who support its construction but do not necessarily have a strong ideological commitment to it. Groups targeted for pressure include contractors working on construction, banks and financial backers, and donors to the Atlanta Police Foundation.

According to Stop Cop City Solidarity, targets who have withdrawn participation in the Cop City construction include its original general contractor Reeves Young Construction, project management firm Atlas Technical Consultants, subcontractor Quality Glass Company, and Atlanta Police Foundation board member Claire Sterk, an Emory University professor.

The State’s Diversity of Tactics

Officials committed to building Cop City haven’t stopped at legal challenges to the ballot initiative. As one might expect of a massive project to strengthen the police devised after the 2020 uprisings, the full weight of the city and state’s repressive means has been placed upon its opponents. In January of this year, police killed forest defender Manuel “Tortuguita” Terán as he sat in a tent in a forest encampment protesting Cop City’s construction. An autopsy showed Terán was shot 57 times in the police raid, and no officers were charged.

More than 40 protesters were charged with domestic terrorism after a weekend music festival that Cop City opponents held in the forest in March. In May, city and state police raided and arrested three members of the Atlanta Solidarity Fund, which is a longstanding bail fund that has helped Cop City protesters and others arrange for bail after arrests. And last month, the Atlanta District Attorney and the Georgia Attorney General charged 61 activists under the state’s RICO statute, a law designed to go after organized crime.

“Obviously, the repression has been terrifying,” Peck said. “That’s what they’re trying to do. They’re trying to sap our energy, sap our resources, scare us, and make us feel burnt out.”

But there is a sense among activists that the state, in the face of mounting critical press and public scrutiny, is reconsidering its strategy: a recent action at the Cop City site, in which five members of clergy physically blocked construction vehicles, resulted in a halt of work for the day and clergy members being charged with only misdemeanors. “I think that is potentially a sign that the state knows it’s overplayed its hand and is pulling back on these ridiculous charges that even mainstream legal scholars are calling an absurd bit of government overreach,” Peck said.

There is Power in Numbers

In advance of the action, Block Cop City organizers will train participants with two days of direct action tactics, including de-escalation techniques and how to make decisions on the fly. Planners expect over a thousand participants, and due to the nature of the event, there is a lower threshold of participants under which the event will not go forward in the interest of keeping people safe.

Peck describes the plan as a catch-22 for the state: if the police charge a thousand people with terrorism over engaging in nonviolent civil disobedience in the spirit of Martin Luther King, Jr., in Atlanta, a birthplace of the civil rights movement, there will be massive international outrage and it will not only clog up the legal system but further delegitimize both the police and the Cop City project. If protesters aren’t charged at all, or only with minor offenses, it shows how unreasonable the heavy charges imposed on activists earlier this year are and makes their acquittal more likely. And either way, construction of Cop City will be severely disrupted.

Part of Thursday’s event split the audience into small groups, with people discussing and making plans together over food and drinks provided by Food Not Cops. More than a dozen people there expressed interest in going to Atlanta for the event, and others proposed local events in solidarity.

Jamie Peck had driven straight from Portland, Maine earlier in the day to reach Burlington for the event, and her whirlwind tour next takes her to upstate New York with little time to rest in between stops. “I’m a little tired,” she says. “But I love doing this, and there’s nothing I’d rather be doing right now.”

Patrick is a writer and organizer based in northern Vermont. He is on the editorial collective for The Rake Vermont.