Halloween-themed signs and chants accompanied yesterday’s rally in support of unionizing graduate student workers at the University of Vermont. Despite the rain, more than one hundred grad students and allies attended the event.

“Graduate students are fed up,” said Lily Russo-Savage, a Ph.D. candidate in neuroscience who organizes with UVM Graduate Students United (UVM GSU). She and others have highlighted the need for livable wages, improved health and dental benefits, as well a robust grievance procedure and protections for international students.

Earlier that day, UVM GSU officially notified the Vermont Labor Relations Board (VLRB) of its intent to unionize. The VLRB has jurisdiction, as opposed to the National Labor Relations Board, as UVM workers are considered state employees. This isn’t the first attempt to organize graduate student workers at the university, but organizers are confident that this effort will succeed. The union reports more than 400 union cards have been signed so far, which they estimate to be a significant majority of all graduate student workers on campus.

One difference from previous organizing drives is how materially worse off graduate students are now. Speakers at the rally cited excessive teaching and research workloads, often exceeding contractual hours, with stipends unfit for the increasing cost of living in the Burlington area. They shared stories of housing costs accounting for well over 50 percent of their income — unsurprising, given median rents in Chittenden County have risen 29 percent over the last five years. They recounted having to choose between medical procedures or food: UVM itself estimates one in five students are food insecure. Others reported being unable to find accessible child care.

Another difference working to UVM GSU’s advantage is the campus is more unionized than ever. UVM Staff United, which represents 1,400 clerical technical, specialized and professional staff, is, at least for now, the newest recognized union on campus, having won recognition in 2021 and its first contract in 2022. Union solidarity was on show at the rally, featuring speakers from UVM Staff United and United Academics (which comprises faculty), as well as Scoopers United, the union of workers at Ben & Jerry’s Church Street location.

UVM GSU also finds itself in good company across the country, as graduate student union formation has picked up pace over the past several years, even in the South. The weeks-long coordinated strike by graduate workers at ten University of California campuses late last year sent shockwaves from coast to coast.

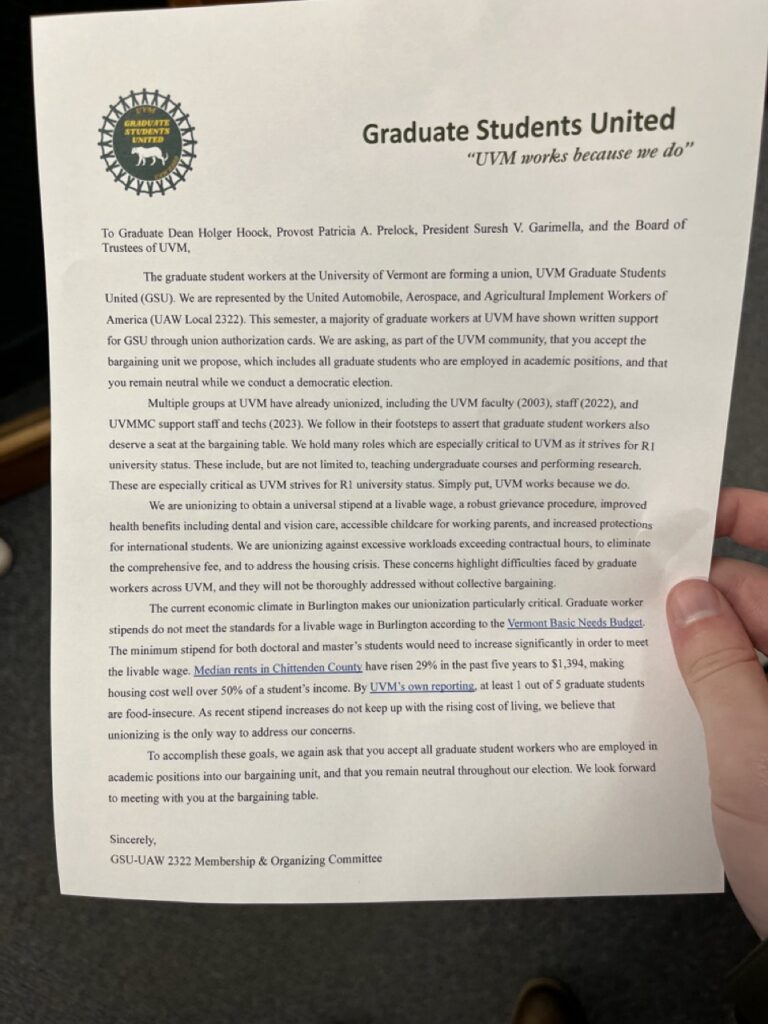

Despite the broad support from labor and the community, much work lies ahead. UVM GSU is currently pushing the administration to commit to neutrality in the run-up to the election, a common demand in these situations — but one that has not yet been met.

In an October 25 letter to graduate students, Provost Patricia Prelock and Dean of the Graduate College Holger Hoock made the administration’s position on graduate worker organizing clear: “UVM has serious concerns about a graduate student union being in the best interests of either our students or the university. This position is based on the unique relationship between the university and its graduate students.”

The letter continues, “UVM believes the graduate student relationship is primarily and predominantly an educational and mentoring relationship… the primary purpose of these positions is to help students make steady progress toward their graduate degrees… the inherently individualized approach to graduate education does not lend itself well to a “one-size-fits-all” collective bargaining approach.”

These arguments are almost identical to those issued by management at other universities. But for graduate workers finding it hard to keep a roof over their heads, UVM’s trumpeting of “the inherently individualized approach to graduate education” rings hollow. Russo-Savage said that the messages from the administration “undermine our legitimacy as workers, [with management] trying to say that we are gaining experience and that should be enough for us, rather than livable working conditions.” She also said the union has heard from international students frightened by the university’s rhetoric. “They’re scared for their status as students in the US, and are worried that they will be sent back to their home countries,” she said.

One union organizer spoke to the crowd about how the existing shared governance model, which UVM prefers, was not up to the task of representing and fighting for graduate students. Baxter Worthing said he was in the Graduate Student Senate (GSS) for years, during which, despite the senate’s efforts, pay and benefits never caught up with inflation, let alone reached a living wage. “I’ve met first-year grad students that moved here and can’t find housing that they can afford. I have friends that have taken second jobs that are on food stamps in order to afford the cost of living here in Burlington while they do their graduate research and teaching,” he said. “And I have international student friends that spent four or five years in graduate school and can never afford to fly home and visit their family. I told every single one of those administrators these stories and not one of them had the courage to stand up and challenge the status quo. So I guess we just have to do it ourselves.”

Worthing noted that as soon as the GSS started seriously discussing forming a union, UVM changed its tune. “The moment we started talking about unionizing, the administration started promising us changes,” he said.

Graduate student workers are central not just to educating undergraduates, but to UVM’s larger ambitions to ascend the rankings of public research institutions, and with it public and private grant dollars. As they marched to Waterman Hall after the rally, they demanded to be compensated in a manner befitting the importance of their labor.

Matt Moore is a writer from Vermont. He is on the editorial collective of The Rake Vermont.