Welcome to the second of our four-part series on the tenure of Miro Weinberger. See Part 1 here.

Rental Vacancy Rate, Chittenden County, 2000-2010: 1.8% – 3.6% (+1.8% change)

Rental Vacancy Rate, Chittenden County, 2010-2019: 3.6% – 2.0% (-1.6% change)

With the Progressive Party still in tatters from the dismantling of the Kiss administration and the new administration basking in an aura of accomplishment from announcing tech and childcare initiatives, as well as having restored the City’s credit rating by seeking settlement with CitiFinancial, Weinberger won a second term with ease against Progressive challenger Steve Goodkind, a former public works director who launched his campaign without a specific agenda and failed to make any tangible policy critique of the incumbent.

At his State of the City Address following his reelection to a second term, Miro boasted of the City’s sterling credit rating as well as savings to his constituency: the first, a “major reorganization” of the Burlington Electric Department, was cash-positive to the tune of $1 million in savings on labor costs through a euphemistically-titled “voluntary retirement opportunity” wherein 10% of its labor force was reduced without layoffs. Rather than replace said voluntarily retired jobs, Weinberger’s appointee to head the Electric Department (Neale Lunderville, a budget-slashing conservative named one of Vermont’s “top Republican Influencers” by Ballotpedia) phrased it as “allowing the organization to do more with less.” Before the end of Miro’s mayorship, the historically stable electric department would announce multiple unprecedented rate hikes.

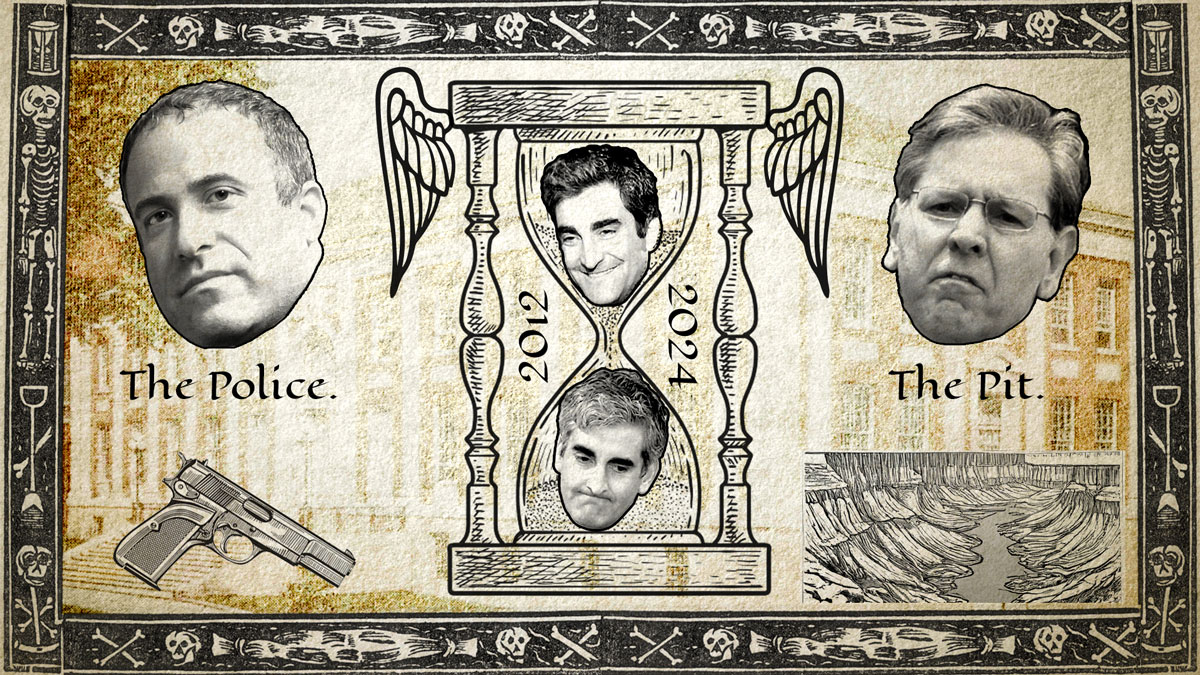

Weinberger also had a new hire to announce: Police Chief Brandon Del Pozo. Del Pozo, formerly an NYPD officer from Brooklyn, promised to fit perfectly into Weinberger’s vision of a data-driven, business-friendly Burlington: Del Pozo had been a rising star in NYPD Commissioner William Bratton’s NYPD, which doubled down on the “broken windows” philosophy of community policing in concert with the CompStat program of using computerized databases to log and track the most minute of crime statistics, as seen and critiqued on the television program The Wire.

Weinberger left no opening for conjecture: an expanded police force under Del Pozo, using the “CommunityStat” office Weinberger claimed to be pioneering, was to be seen as a crown jewel in his administration’s efforts to combat one of Burlington’s (and Vermont’s) greatest challenges: a gathering wave of opiate abuse and opiate abuse related crime. Held up as a bulwark against this, Del Pozo was declared by Weinberger to be the messiah of “21st Century Policing” which would, in turn, stem the tide of drug abuse and drug abuse inspired crime. Del Pozo advertised himself as a philosopher, a technocrat, and a reformer who would be making big waves in a small community like Burlington; he did, but more on that later.

Although “21st Century Policing” was his closing promise, Weinberger hammered upon another ambition as the most urgent to his administration: securing financing to redevelop city infrastructure and, more importantly, housing. Citing the need for a robust effort to maintain and improve infrastructure, Weinberger segued into “the greatest housing and job opportunity before us… the redevelopment of two central blocks of our downtown dominated by an outdated and declining mall.”

Del Pozo got off to a rocky start. In March 2016, Burlington Police Department officer David Bowers shot 76-year-old Phil Grenon a week after Grenon had received an eviction notice from the Champlain Housing Trust-owned subsidized housing property where he was a tenant. After receiving his eviction notice, Grenon notified his treating psychiatrist at Howard Center, the state’s largest private non-profit mental health services contractor, that in case of police attempting to dislodge him he would protect himself with knives. The Howard Center did not notify the BPD – a week later, BPD officers took three hours attempting to communicate with Grenon before Del Pozo gave the order for them to enter the apartment, at which point officers tased, then shot a knife-wielding Grenon. Four years later, the shooting was ruled “preventable” by a report which, among other things, revealed there was no communication between Howard Center and BPD regarding Grenon’s mental state, level of medication, or stated belief to mental health professionals in the months beforehand that police would come to his apartment and kill him.

In December of 2016, two years or so after Weinberger and Devonwood Properties Developer-in-Chief Don Sinex gleefully unveiled development plans for a $200 million redevelopment of the then-standing Burlington Town Center mall (referred to as the “CityPlace Project”) at a showy press conference, Sinex applied for a permit for exactly one half of the development. Although he said at a news conference that he had raised all $200 million in financing for the development – this being necessary per the city’s requirements for development – Sinex did not say where or who he had raised this money from, and by the time of application for this permit any and all plans for the second half had been drastically scaled back to account for cost. The city of Burlington took in almost $400,000 in fees for the permit application. Sinex expected construction would take approximately 18 months – a key figure, as a large portion of his development plans were contingent upon completing construction before a lucrative lease with the University of Vermont Medical Center expired.

Meanwhile, another large building in Burlington’s downtown was in the news for all the wrong reasons: built in 1927 and added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1988, Burlington’s Memorial Auditorium had for two decades prior been undermaintained by the city; in 2017 it sat completely vacated a year after the city deemed it structurally unsound for occupancy and gave its tenants a move-out notice. Five years earlier, at the beginning of the Weinberger mayorship, estimated repair costs for the structure sat at $4 million; over the course of said five years, the city saw fit to do little to nothing to refurbish or repair the 20,000-square-foot building to a point where it might generate revenue or civic vitality for Burlington and its residents.

The abandoned Moran power plant also saw discouraging news in 2017. Years after the then-new mayor axed promising plans to redevelop the plant, then set forward with an endorsement of the improbable and inexperienced New Moran Initiative, the city decided to cease discussion with New Moran Initiative on granting it Tax Increment Financing in the same way it had Don Sinex’s Devonwood Investors. With this halted, the city under Weinberger began its plans to go through with what it had threatened it might all along: demolishing the plant, returning no value or development to the waterfront district which the mayor had once identified as a key priority, saying this: “I am confident that today’s decision to shift our focus away from the long-standing goal of full Moran redevelopment, though difficult, will open up new, creative options for the site that will finally allow the public to fully reclaim the northern waterfront from its post-industrial past.” The end result, 5 years later, would be demolishing the plant but leaving its stripped frame standing, painted red, illuminated by a handful of colored lights and adorned by a few metal swings.

In spring of 2017, despite having told the press and the city several times over that the CityPlace development was fully financed while refusing to disclose who or where the financing came from, Don Sinex and Devonwood Investors came forward to disclose that they had partnered with Rouse Properties, a New York City-based national mall owner and operator (and subsidiary of Brookfield Asset Management, a Canadian multinational real estate investment firm), and were weeks away from closing a six-month process of securing the funding which had been, according to Sinex, already secured. All that was outstanding was a $200 million construction loan to cover the entirety of the project’s actual costs which Sinex assured the press would come any day, stating that this was “fairly typical” of such projects. That October, the city signed a development agreement with a custom LLC, “BTC Mall Associates LLC,” chartered in Delaware for tax purposes, to move ahead with the project.

Also in October 2017, Weinberger’s handpicked Boy Wonder Police Chief came under further scrutiny as the ACLU condemned the BPD’s practice of raiding homeless encampments, seizing and destroying personal property of the inhabitants and forcing them to relocate without adequate notice, thus violating (according to the ACLU’s letter) the US Constitution’s Fourth, Eighth, and Fourteenth amendments. The letter, sent to City Hall, namechecked Del Pozo personally, calling into question his interpretation of the law before demanding the encampment raids immediately be ceased as a matter of policy practice. The city did not respond, and the ACLU filed suit. The next homeless encampment sweep, scheduled on a Thursday at a site on Burlington’s Sears Lane, was delayed due to Del Pozo’s complicity with the ACLU’s concerns over the storage of personal effects and the ability of those at the encampment to find alternative temporary shelter. The encampment was then summarily dislodged – to another site a few hundred feet away. When asked, Del Pozo claimed he was “unsure of where the campers went,” as well as that “disbanding the camp may have been enough to disrupt the pattern of safety incidents.” He followed up, “Whatever was catalyzing the problems at that encampment, we’ll see if those problems catalyze at the new location.”

By his second term, Weinberger had completely abandoned any pretenses that Burlington Telecom might hope to be regained by the city through a cooperative ownership bid; although such a cooperative ownership bid was well within the confines of their contract with Blue Water Holding, at no point in the 5 years of said contract did the Weinberger administration attempt to seek such a resolution, in fact urging the City Council to vote against a $12 million bid from a local co-operative consortium called Keep Burlington Telecom Local – in spite of this, a majority of City Councilors voted for the Keep BT Local ownership bid in October 2017; the second-place offer from Ting, garnered one less vote. Only one vote went to an offer from Indiana-based Schurz Communications, which was eliminated from bidding.

Two weeks later, in an extremely late-night session and on the heels of Citibank threatening to sue the city should it choose Keep BT Local, City Council delayed its vote to choose between Keep BT Local and Ting for another month as pro-Miro Democratic Councilor Karen Paul asked to recuse herself from the vote, citing “a professional conflict” which she refused to elaborate on, only saying that the issue “has nothing whatsoever to do with the parties interested in purchasing Burlington Telecom.” The next week, Paul quit her job so as to be able to vote against Keep BT Local in the next round of voting, ensuring a deadlock; upon further request to reveal the nature of her now-obsolescent professional conflict, Paul denied any comment. With the City Council deadlocked, a proposal for Ting and Keep BT Local to combine efforts was made.

The effort to combine bids failed, however, and two weeks later, in a closed-doors executive session of City Council, Burlington Telecom was sold to Schurz Communications and a private equity firm from New Jersey for $30 million. During the period leading towards the sale, City Council members were forbidden from communicating directly with potential buyers; however, when a similar rule was proposed for Weinberger and his administration it was shut down. When asked why the city had changed horses to Schurz seemingly out of nowhere, Weinberger cited a provision in Schurz’s offer which promised insulation from further legal action against the city regarding the telecom’s operation.

With the final vestiges of the prior administration’s mess finished, Weinberger and his administration turned their eyes to a prospective third term, seemingly full of promise: a large-scale development downtown to revitalize the urban core’s economy, a data-driven police department headed by a hotshot young chief, a downturn in local opiate overdoses amidst a state-wide opiate explosion, and a City Council which – if not wholly pliant – was able to be maneuvered towards the Weinberger administration’s agenda.

Cocktail Hell is a nameless service industry professional in Vermont.