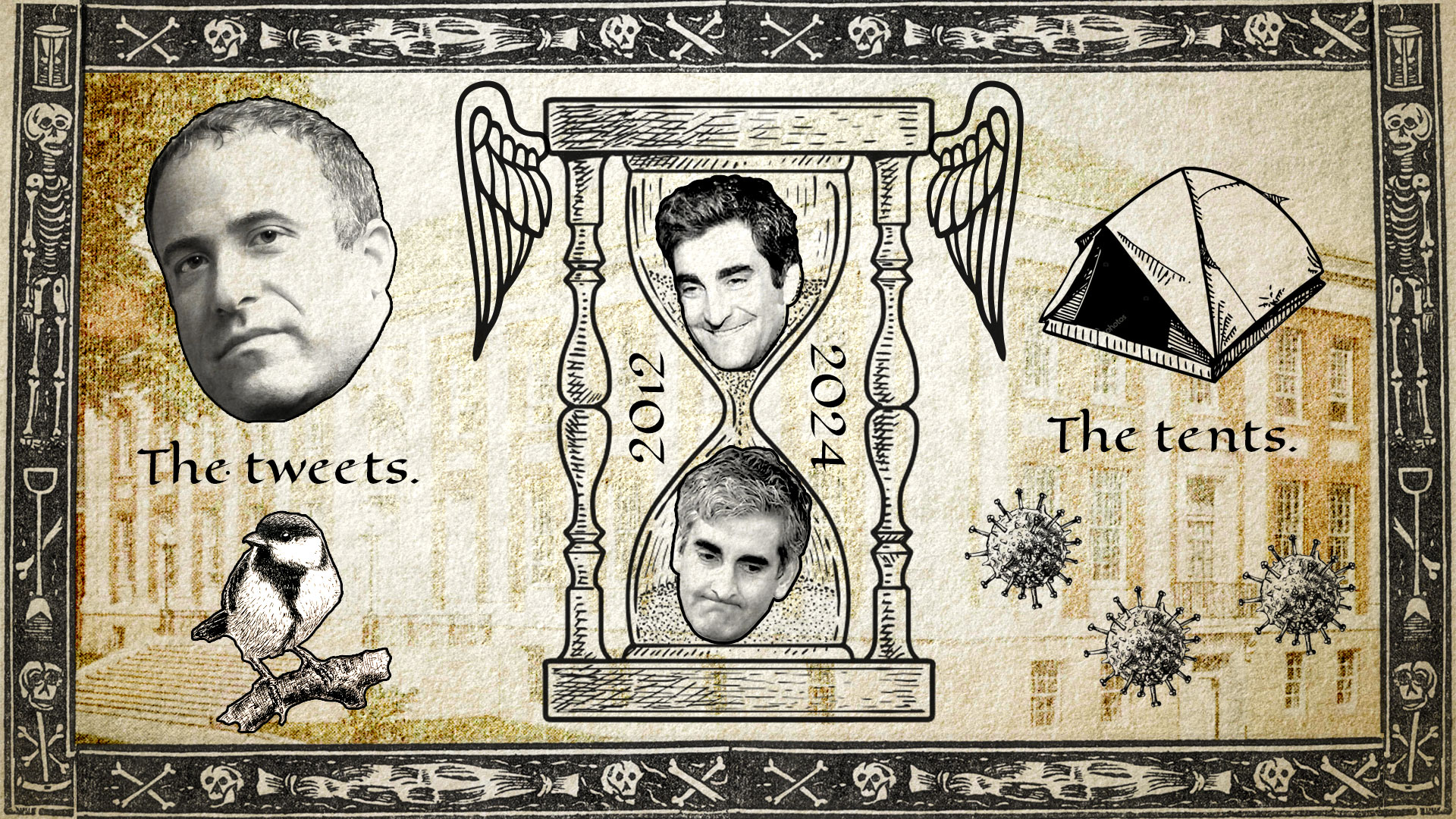

Welcome to the third of our four-part series on the tenure of Miro Weinberger. See Part 1 here. See Part 2 here.

Chittenden County Point-In-Time Homeless Population Count, 2012: 384

Chittenden County Point-In-Time Homeless Population Count, 2023: 758

The 2018 Burlington Mayoral election saw no official Progressive Party candidate running against Weinberger. Instead, he faced two independent candidates: the first, Carina Driscoll, Bernie Sanders’ stepdaughter, one-term School Board member, partial-term Burlington City Councilor, and former advisor in Weinberger’s own administration; the second, Infinite Culcleasure, a community organizer with ties to the Burlington Progressive Party. Upon winning the Progressive nomination without asking for it, Driscoll asked Culcleasure to drop out; he did not, stating, “being coerced to drop out of a campaign for public office has been one of the most anti-democratic adventures I have ever experienced.” Meanwhile, Weinberger raised $125,000 to his opponents’ combined $69,000 in campaign funds, took 48% of the citywide vote, thanked his opponents, and resumed his mayorship.

The developer-turned-mayor’s greatest ambitions, however, were turning out to be more difficult to bring to fruition than previously assumed. Directly after Weinberger’s reelection, the city approved adding apartment space to the detriment of retail space in CityPlace’s redevelopment plan, but despite this and lagging demolition efforts by the summer of 2018 the already-approved foundation had yet to be permitted or laid for new development. The demon delays that the joint venture under Don Sinex had run into: both removing hitherto-unconsidered asbestos, discovered during demolition, and undisclosed “issues” arising between Sinex and the contractors he had hired to do said demolition, issues which at one point were so great as to prompt him to threaten firing the contractor.

Additionally, Sinex’s Devonwood Investors and their partner Brookfield (which had by that point fully absorbed Rouse Properties) were yet to secure the bulk of the financing for the project through the $200 million construction loan which four years prior Sinex had not disclosed requiring, and the year prior he and Brookfield had been confident was forthcoming. City officials including the mayor were beginning to express their frustration to the developers, and eventually – despite lacking the appropriate permiture or financing – City Hall pushed through approval for the concrete foundation to be poured without those prerequisites.

Additionally frustrating the Weinberger City Hall’s plans: in July of 2018, two months after the mayor mentioned “21st century policing practices” in the lead statement of his State of the City address, the man responsible for overseeing them – Police Chief Brandon Del Pozo – suffered a debilitating bicycle accident in Keene Valley, New York, fracturing multiple bones in his ribs, shoulder, collarbone, and skull. The police department named Deputy Chief Jan Wright as his interim replacement, but much of the direction of the department – overseeing its CompStat-style ‘broken windows’ policing initiatives and placing high emphasis on beat patrols – was custom built for and by a chief with Del Pozo’s experience. Luckily, the outlook for him to make a full recovery was rosy.

That fall, having secured the city’s go-ahead to pour CityPlace’s foundation without funding or permiture and very much still having yet to pour any foundation, Don Sinex went to the press and blamed Brookfield for the lack of foundation poured. Brookfield, at that point 51% owners of the project (having been brought on to secure the financing that Sinex in 2016 insisted was fully present) refused to authorize his submission of documents to the city, which were key to receiving permiture to pour foundation. Sinex refused to disclose the reasoning behind Brookfield’s refusal to authorize him to apply for the permit. Despite all this, the mayor remained cautiously optimistic that the project would get back on track, stating by December 2018 that Brookfield had “a good track record,” with Sinex adding that he was “very close” to getting all the funding for the project. Several months later, in February 2019, Brookfield, previously a silent partner in the CityPlace project, stated that it would be assuming control of development but refused to provide further details to the public beyond that the project was in full review and that they hoped to break ground that spring.

That spring held some fresh surprises: less than a year after Police Chief Brandon Del Pozo returned to work from his traumatic bicycle accident, Burlington Police officer Cory Campbell punched 54-year-old Douglas Kilburn three times in the right temple, hospitalizing and eventually killing him. State Chief Medical Examiner Steven Shapiro ruled the death a homicide, but not without intense pushback from the mayor and his handpicked chief of police.

Privately, Del Pozo went on the offensive before Shapiro’s findings were even announced, emailing Vermont Health Commissioner Mark Levine that he and the mayor believed Kilburn’s autopsy report to be inconsistent with Shapiro’s death certificate ruling. In Del Pozo’s words, verbatim from emails obtained by Seven Days, “Our concerns is [sic] that the report of the autopsy does not support a conclusion of homicide based on any [legal] standards.” Later in his email to the Health Commissioner on his and Weinberger’s behalf, Del Pozo went on to write that there was an “urgent and acute” need to clear things up, as “it will bear greatly on the career and life of a police officer,” and also “cause people to impugn the quality of care offered by Vermont’s flagship hospital,” as well as “imply that the police used homicidal violence… …regardless of the legal outcomes.”

Levine, concerned, called Del Pozo to discuss further and clarify his office’s role. Seven Days reported that the president of the National Association of Medical Examiners found Del Pozo’s position “badly mixed two different standards” — legal and medical — regarding determinations of the cause of death.

In addition to his private correspondence with the health commissioner, Del Pozo continued crusading in the public record as soon as Kilburn’s death certificate was released, saying, “it is possible to rule something a homicide in a death certificate without knowing even precisely how the person died,” to which the Department of Health very reasonably asserted via email that it had, in fact, determined the cause of death if not the exact mechanism. During a press conference, Del Pozo doubled down on his line of questioning in his private correspondence with Levine, strongly asserting there was a meaningful difference between the medical and legal rulings of homicide. Nonetheless, the Vermont State Police opened an investigation into Kilburn’s death.

A week or so later, state officials began criticizing Weinberger and Del Pozo for their efforts to question Shapiro’s findings and tamper with their announcement. Thomas Anderson, head of Vermont’s Department of Public Safety, called it “completely inappropriate,” while Jason Gibbs, the Governor’s Chief of Staff, said it “did not feel right.” Anderson added that the Department of Public safety had to “repeatedly advise Delpozo [sic] that he has recused his Department from this investigation,” and that for him to be “inserting himself in this matter is very troubling.” Gibbs noted the mayor’s chief of staff had attempted contact in the hopes of “[having] us intervene to pause the release” of Shapiro’s findings, saying “The mayor’s office wants us to intervene in the matter…” and that “This does not feel right to me, on any level.”

Del Pozo and Weinberger expressed no contrition in response, the police chief citing his attempts to have “one echelon of government [ask] another echelon of government to explain its rationale” as “democratic accountability,” the mayor adding that this was “an attempt for us to make sure this report was getting the proper attention… …because we knew that a report that was incorrect would have long, significant consequences that would be difficult to reverse,” in joint statements to the press. Kilburn’s family would file a wrongful death case with the city the following year, which would then be settled for $45,000 the next year.

Two months after Kilburn’s death, in May 2019, two Burlington Police Department officers had an excessive use of force lawsuit brought against them for knocking a 24-year-old Congolese immigrant unconscious and then tackling his brother to the ground after he requested the officers stop, fracturing the former’s jaw and eye socket. The night before, a different officer had knocked a different Black man unconscious by throwing him to the ground, which also incurred a separate excessive use of force lawsuit. One of these cases would be settled by the city for a total of $750,000; the other suit is still pending as of the time of writing. One of the officers involved in the incident with the two brothers, Cory Compbell, was the same implicated in the homicide of Douglas Kilburn, while the officer principally involved, Jason Bellavance, eventually received $300,000 in severance pay to leave the Police Department despite being officially cleared of any misconduct or wrongdoing.

The CityPlace project, meanwhile, continued to flatline throughout the spring, despite Brookfield Properties’ having wrested control of the project from Sinex. Although a March memo from the city asserted Brookfield would begin construction in June, by July they were eyeing “extensive redesigns,” which according to Weinberger would concern “the size and scale criticisms of the project.”

June also saw more controversy for Del Pozo, whose police were again in the news, this time defending their actions in a recently-released video of a Burlington Police officer using pepper spray on a 6-year-old girl; the incident in question had taken place the year before when the child had destroyed neighbors’ property with a rake and a butcher knife. Police, upon apprehending the 6-year-old brandishing a knife, took several minutes to wait for backup and to consider tactics in responding, considering use of a stun gun and batons before six officers in total assembled, eventually settling on the use of pepper spray due to fears for their own safety as well as the safety of onlookers and the child herself. When reached for comment, Del Pozo cited the use of pepper spray as the best option available and highlighted officers’ concerns for the child’s safety. Weinberger, for his part, added that it was a “very challenging and unusual situation for any Police Department,” and that “officers were able to resolve this incident without any lasting injury to the child.”

As June of 2019 came to a close, marking a year since Del Pozo’s bicycling accident, one can only assume that the police department hoped to move forward from what by all accounts had been an embarrassing and trying series of events compressed into that 365-day period: the bicycle injury, the Kilburn homicide ruling and humiliating exposure of Weinberger and Del Pozo’s back-channel politicking, the multiple excessive uses of force, and the pepper spray incident. There was the feeling that the following months would be critical for rebuilding trust with the public in Burlington’s 21st-Century Police Chief.

July, however, had other ideas. A former city council candidate and Burlington Progressive Party Chair (and, full disclosure, one of The Rake’s founding members), noticing that a particular anonymous Twitter account had seemingly been created specifically to target them, contacted Burlington alt weekly Seven Days with suspicions and evidence that Del Pozo might be behind the account. This was not without precedent: two years earlier, Del Pozo had taken to his personal Facebook account to respond to an 18-year-old woman’s post regarding a highly publicized encounter she’d had with Burlington Police; his response, while unprofessional, was in keeping with his social media use: Del Pozo ran the Burlington Police Department’s Twitter account personally, using it to reach out to individuals via both public posts and direct messages, sometimes in a capacity which made those contacted feel uncomfortable. When Seven Days contacted Del Pozo about the anonymous Twitter account, though, he issued a definitive blanket denial, replying in the negative as many as twelve times throughout the interview as to whether the account and its posts were his creations.

Five days after the Seven Days interview, on July 28th, Del Pozo came to Weinberger’s home to discuss the accusation: namely, that it was entirely true, and that he had just very publicly lied to the press. Weinberger immediately told the chief he was to be placed on paid administrative leave. Shortly thereafter, without notifying the press, City Council, or the police commission, Weinberger launched a secret investigation spearheaded by the city attorney and city HR Director to produce an exculpatory framework for Del Pozo’s paid leave; on August 2nd, after internally deeming Del Pozo’s actions to be “linked to an underlying medical condition,” city hall announced that Del Pozo was on a “Family and Medical Leave of Absence.” The target of Del Pozo’s harassment would go on to suffer from post-traumatic stress intense enough to require long-term disability leave and benefits.

While Del Pozo was on leave, the Burlington City Council saw representatives from Brookfield Properties confirm the Cityplace project would be meaningfully scaled back from its already-scaled-back plans under Don Sinex, and although they had proposed a beginning to construction in June their Vice President did not have any information as to what changes might be made to the plans or whether there was an actual timeline, only committing to “some action in the near term, in the next year.” In September Weinberger laid out a requested list of steps for Brookfield to take on the project, principally demanding a $50,000 payment to the city and an actual development plan by the end of October.

Del Pozo returned from his paid leave in mid-September, having been cleared to return to duty by his own personal doctor as well as a city-appointed independent medical examiner. In lieu of any public disclosure of his involvement in the targeted online harassment of a Burlington resident, Del Pozo received a personal admonishment from the mayor and was told any further offense would result in termination, but that his service had “otherwise been exemplary.” This seemed to put to bed any notion that there would be any further discipline or discussion forthcoming from the mayor regarding Del Pozo’s conduct, or the conduct of his department.

On October 28th, Brookfield presented a series of preliminary designs to City Council without committing to any specific development plan, start date, or timeline; a month later, a preliminary timeline from Brookfield slated development to be finished by February 2023 at a cost of $120m, a little over half the initial cost projected by Don Sinex. Although to some observers this seemed to be repeating a prior-established pattern of the project being promised to start at a later date, then undergoing scaling back due to financial concerns, then being delayed, then receiving a new timeline and start date, then undergoing more managerial turbulence and delays, and so forth and so on, the city and mayor were once again optimistic that this would put the project back on track.

November 2019 brought further reason for optimism: Burlington’s City Hall Park, closed for renovation for years and for years prior a fairly unadorned green space with a fountain and a few walkways, reopened with public bathrooms, new benches, small gardens, and a new fountain festooned with colorful lights. The mayor also announced that since his inauguration in 2012 more than 900 new homes had been created in Burlington, and added that this “gives me hope that the strategies we have been using to address our housing crisis are starting to work,” despite which the cost of rent and housing in Burlington was demonstrably keeping almost directly apace with inflation if not outpacing it.

December brought some different sorts of press events. The activist whom Del Pozo had harassed online published a statement on their personal website enumerating the evidence they had that Del Pozo was behind the anonymous account targeting them; the day after, Seven Days once again reached out to Del Pozo about the allegations. A deputy chief called the paper back a day later inviting them to speak with the chief the next day for comments on the record. In the ensuing interview, Del Pozo admitted to being behind the account, claiming that he had experienced a heretofore-undisclosed brain injury due to his bicycle accident (a claim which the actions of various medical professionals ran counter to, Del Pozo having been cleared to run an entire city’s police department multiple times over by this point) and that while he could not share any actual diagnosis of this brain injury that it had “resulted in a lapse of judgment where I made a mistake that I regret,” and that he had “responded to negativity with negativity in a way that doesn’t become a chief of police.”

Despite Del Pozo’s lengthy pre-bicycle-accident history of highly-vocal and highly-visible use of social media, Miro Weinberger’s comments echoed the chief’s claims of psychological issues stemming from a brain injury, saying “Mental health challenges are serious issues among public safety personnel,” in the understatement of the year (if not decade or century). Repetition notwithstanding, it bears noting once more that the target of Del Pozo’s harassment was sufficiently traumatized to receive a diagnosis of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and require long-term disability benefits.

In addition to calling for compassion in responding to Del Pozo anonymously harassing a Burlington resident and lying about it to the press, Weinberger applauded Del Pozo’s honesty in admitting to it after further pressure – ultimately, though, the damage was done and a few days later he announced Del Pozo’s resignation, stating “I will miss him greatly, and I believe Burlington will as well,” to the media. Deputy chief Jan Wright, who had replaced Del Pozo while he convalesced from his bicycle injury the year prior, was named interim chief in the hopes that she could use that experience to hold things together until either being named Chief of Police outright or some other suitable candidate was chosen.

The same day that Wright was named acting police chief, she informed Weinberger that she was behind a Facebook profile named ‘Lori Spicer’ which she used to defend the embattled police department in online discussions. Former Colchester police chief Jennifer Morrison was appointed as the police department’s interim chief later that week, and Wright was put on an eight-day-long administrative leave as the city attorney combed posts by ‘Spicer’ for legally-actionable content. Upon being appointed, Morrison stated “this is a world-class police agency,” a statement which could read as initially confusing if not for the contrast provided by Colchester police under her tenure there. In 2014, Morrison’s first year as chief, a Colchester police detective was convicted of stealing opiates and at least one firearm from the Colchester evidence vault for his own use and distribution. In 2016, a police dispatcher for Morrison’s department was let go after facing criminal charges for compromising a federal investigation by allegedly sharing confidential information with a sex worker he had hired.

The city investigation into Jan Wright’s social media use found that Wright had been using, in addition to the ‘Lori Spicer’ account, another account under a false name, ‘Abby Sykes,’ but declined to share with the public more than a handful of posts made under the Sykes or Spicer accounts, simply concluding that there was “no indication… …of obsessive or dangerous behavior.” The city, citing difficulty accessing the accounts (Wright professed she had forgotten her passwords to the two accounts), stated that in its eight day investigation there was not “extensive additional activity” outside of the handful of the posts it had disclosed to the press.

A few days later, the press – having done a basic manual search of the Spicer and Sykes accounts’ activity on multiple Facebook pages – uncovered extensive additional activity, including questioning the necessity of African Americans on the Burlington Police Commission.

Weinberger responded by saying he was “not shocked” at the “problematic and troubling” discovery, but said of the city’s investigation that it was “extensive,” adding he was “not happy to hear that quickly [the press had] been able to find significant additional posts.”

By the end of 2019, there were clear contra-indications regarding Burlington’s financial health, indicators providing context for the mayor’s prior two terms but also proving crucial to an understanding of his terms to come. In figures averaged from 2015-2019 by the United States Census’ American Community Survey, Burlington’s median household income came in at a number over $10,000/yr beneath Vermont’s state median income and over $20,000/yr below Chittenden County’s median income. In the same four-year period, however, the Burlington-South Burlington per capita personal income had grown each year, with the largest rises coming in 2018 and 2019. Likewise, the City of Burlington’s budget for Fiscal Year 2019 showed a $9.45 million increase in revenues from its 2017 budget.

Further confusing the matter, 2019 saw Burlington’s rental vacancy rate fall from its peak of 6.73% in 2008 to 2.18%. Despite the mayor’s boast of creating 900 new homes since his first inauguration, and a decade-long surge in area rental construction permitting, 2019 saw the lowest amount of new rental construction permits issued in the Burlington area market since 2010. January 2016 to January 2019 saw an average of 349 eviction filings a year in the area; 2019 itself saw a 18% increase in eviction filings from that average, up to 413. While perhaps tangential, the period of 2015-2019 also saw an initial growth of fatal opioid overdoses among Vermonters due to the emergence of fentanyl in its drug markets, with fatal fentanyl overdoses going from twenty-eight in 2015 to one hundred in 2018 and ninety-eight in 2019.

The data points a picture of an administration which, to this point, was chiefly preoccupied with boosting profitable economic activity within the city’s confines and ignoring addressing in any relevant way the chief concerns of its constituency other than giving them lip service: despite having been in power to pursue their agenda for the better part of a decade and projecting the image of having done so largely successfully, by 2019 the Miro regency – presiding over the state’s largest city, holding the largest budget – was seeing lower vacancy numbers and higher eviction proceedings, rent staying apace with inflation contrasted with depressed and stagnant wages.

It was with these economic conditions as a backdrop that Miro entered a new decade and the final year of his third term, with CityPlace still yet to begin construction, a police department under scrutiny for excessive force, one police chief dismissed, and another on administrative leave under investigation for the same activity their predecessor had been dismissed for. With an eye towards securing another term in a year and his legacy on the line, it seemed the mayor needed key victories, or at least the appearance of them, on one or several of these fronts. There were signs of a bad start: in the first three months of 2020, area eviction filings equaled 399 in total, those three months alone outpacing the last three years’ entire annual average.

Then Covid-19 happened. In early March 2020, Governor Phil Scott declared a statewide state of emergency in response to the news of Covid cases growing in the United States. Weinberger, never one to be upstaged, mandated masks, limits on social gatherings, and the temporary closing of local businesses ahead of state guidelines. While providing the outward appearance of responsible governance in the face of unprecedented crisis, these measures did little to insulate against threats to Burlington residents at greatest risk – two Burlington-based nursing homes, Birchwood and Burlington Health & Rehab, provided the state with more than half of state Covid deaths within a few months; worse still, due to minimal oversight a state investigation and independent reporting found – in addition to Covid-related deaths – unreported cases of neglect in residents which contributed to non-Covid-related health outcomes. Ultimately, no corrective or punitive measures were applied by the city.

Throughout the pandemic year, the city continued to curtail key economic activity while withholding financial resources in sight of redress to its most precarious residents, instead allowing state and federal funding to do the heavy lifting. The bulk of the city’s expenditure was $1 million towards the establishment of a Covid-19 Resource and Recovery Center, allocating funds from the sale of Burlington Telecom. The Resource and Recovery Center, as it came to exist, was a phone number and email which was staffed by already-extant CEDO personnel, as well as a page on the City’s website with links to already-extant public resources, all of which were stretched to the point of breaking by a flood of newly-unemployed Vermonters – unemployment rates in Burlington jumped from 2% to 11.5% from March ‘20 to April ‘20, and would take a year and a half to come back down. The other half of Weinberger’s March Covid relief package: waiving interest on late utilities payments and the city’s gross receipts business tax, as well as giving City Hall the authority to make purchases and enter contracts without City Council or the City Board of Finance’s approval.

Without need for financial oversight, funds were allocated haphazardly. A housing triage site at North Beach Campground was set up for 25 unhoused people, and RV campers were rented from a local company at $1000 per week per camper, with more funding going to Anew Place, a religious private organization and favorite housing proxy for Weinberger, for administrative work. In July of 2020, the City applied for $1.3 million in CARES Act grant money to contract Beta Technologies, a then-undefined tech startup, to fashion shipping containers into homeless shelters, also managed by Anew Place. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this went nowhere. By this time, Vermont was in the midst of a 160% increase in emergency shelter populations, compared to an nationwide 8% decrease.

While Weinberger’s City Hall struggled to get emergency relief funding into the hands of a technology startup, Anew Place, and an RV company, all in the name of fighting Covid-heightened homelessness, protests began occurring regularly outside of the Burlington police station and City Hall in response to the May 25th murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin. The protests at first focused on the national outrage around Floyd’s murder, but soon became focused on the Burlington Police Department’s various controversies and abuses. The protests continued throughout the summer, hundreds and occasionally over a thousand strong, and by August began taking permanent residence in Battery Park next to the Police station. In addition to the public marches and protests, hundreds of Burlingtonians had attended the city council’s virtual meetings demanding funding cuts to the Police Department.

Weinberger, in response, announced $1.1 million in cuts to a proposed 2021 police budget of $17.4 million (the budget had gone from $16.4 million in 2019 to $17.25 in 2020). Although around $800,000 of the savings from these cuts would go towards Covid-related tax revenue shortfalls, $300,000 was proposed to go towards creating a new position at the Office of Racial Equity, Inclusion and Belonging, which had been incorporated in February of that year and at the time of this budgetary shuffle had exactly one staff member, its director, Tyeastia Green, conveniently hired from a previous post at a municipal DEI position in Minnesota. In addition, Weinberger appointed the Burlington YMCA’s CEO Kyle Dodson, a fellow Harvard alumni, as “Director of Police Transformation.” As per the city’s website, his work would “help lead the City’s work to forge a new consensus on policing in Burlington.” For this he would receive a $75,000 salary in addition to his pay from the YMCA, from which he would temporarily step away.

At about the same time, seemingly in response to the public outcry, Burlington City Council voted 9-3, with bipartisan support, in favor of reducing the Burlington Police Department’s staffing by almost 30%, electing to reach this reduced cap through attrition via retirement rather than termination of existing officers. At the time of the resolution’s passing, Burlington Police were already below their existing officer cap of 105, with 91 members.

With two of Miro’s three main focuses – a healthy municipal budget ripe for public-private partnership opportunities and a well-funded and well-respected ‘modern’ police force – on the edge of complete catastrophe, courtesy of Covid and public outcry, the third crown jewel of his administration was also once again facing major setbacks. Despite apparent success in the planning stages and minor legal skirmishes accompanying the CityPlace development, in July 2020, the City caught wind that Brookfield Properties was now abandoning its phased construction plans and readying to sell management rights back to Don Sinex and Devonwood.

An incensed Weinberger sent Brookfield’s proxy corporation, BTC Mall Associates LLC, a letter informing them they were in default of their obligations and threatening to sue should plans not resume as intended. Brookfield, when reached for comment, declined; Sinex, via email, promised a press release “sometime soon” and then immediately recanted that “It will not be anytime soon,” an echo of the long-delayed development’s actual construction process.

A month later, despite the City’s threats of legal action, Sinex and Devonwood announced they had bought out Brookfield Properties’ stake in the CityPlace project and were bringing on local partnership with the owners of three of the area’s most prominent construction and contracting concerns. Weinberger, wary of once again being duped, rattled his saber by raising the notion of potential legal action against Brookfield, adding for good measure that this group of developers “has provided no evidence that they will be able to produce better results in the future than a Don Sinex-led partnership has delivered over the last six years.” Despite this, the city took no action against Sinex, and the plans Brookfield had laid out remained largely the same for the new group, save their avowal that there would not be a hotel included in the space, instead stating a preference for increased residential space.

August of 2020 also saw the mayor use his first ever executive veto, overriding a City Council vote to reinstate ranked-choice voting as the modus operandi of municipal elections, including the upcoming mayoral election which Weinberger planned to take part in. Ranked-choice voting had been adopted in 2005, then narrowly abandoned in 2010 in a hotly-contested ballot initiative as part of a Democrat-instigated backlash against then-mayor Bob Kiss. In the 2010 vote, all but two Burlington wards supported retaining ranked-choice – now, a decade later, it seemed timely to readopt the largely popular measure. Weinberger’s veto dashed the possibility of ranked-choice being adopted for the upcoming mayoral election, but it would be on the ballot that March for a public vote.

Meanwhile, Burlington’s Battery Park Movement was not impressed by Weinberger’s $300,000 DEI office job addition, his CEO-turned-Police Transformation Director, or the City Council’s attrition resolution. By September, protestors remained well-established in Battery Park, and had added a list of concrete demands to their decrying of nationwide police brutality: the termination of Burlington Police Officers Jason Bellavance, Cory Campbell, and Joseph Corrow, all of whom had been involved in high-profile local instances of alleged excessive force. In response, Weinberger made vague remarks eliciting sympathy toward victims of systemic racism, but did not address or acknowledge these demands.

As public pressure mounted, facing a reduced police force cap, a raging pandemic, and a silent City Hall, acting Police Chief Jennifer Morrison decided to resign her post, citing a City Council with “no expertise in public safety — only aggressive social activism platforms spoon fed by national organizations” on Facebook and a belief that “Burlington City Council has created circumstances that are antithetical to public safety” to the press. Jon Murad, who had served as a very hastily-appointed bridge between Jan Wright and Jennifer Morrison, was appointed as Acting Police Chief.

In a final act of capitulation after Morrison’s resignation, Weinberger brokered a deal to dismiss the one officer not represented by the Burlington Police Officers Association (the local police union) named in the protestors’ demands, Jason Bellavance. The settlement paid Bellavance three years’ salary – $300,000 – in addition to 18 months of health insurance and three years of service credit towards his pension and retirement benefits. The other two officers, Corrow and Campbell, would remain on the force.

September of 2020 also saw Burlington High School closed due to above-recommended ambient levels of polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, chemicals used in 1960’s-era building materials which are known to cause damage to immune, reproductive, nervous, and endocrine systems, including cancer. Students had just returned to in-person learning and would now go back to remote, further aggravating many in the Burlington area.

Winter fast approaching, high school shuttered, city coffers ravaged by a Covid-stalled economy, protestors in the streets, and Sinex back but in tight with local grandees, Weinberger dug in his heels and went after the only political opponent Vermonters find universally palatable: out-of-staters. Now desperate for anything even remotely resembling a win, the City of Burlington sued Brookfield Properties for, at the very least, public improvement costs. Originally, Weinberger had signed on to reimburse Brookfield for development costs related to the project. Months later, many promises broken, he sounded a different tone: “Our patience is gone now,” he glowered to the press.

October came. After over a month of prolonged encampment across from the police station, one of their demands having been met and the air turning cold, Battery Park occupants packed up and left as the leaves around them turned muddy-hued and died. Granted reprieve from protests, Weinberger also found welcome, if scant and unreliable, news from CityPlace: an application from the newly-christened Construction Devonwood for a new zoning permit with revised plans for a structure much the same as Brookfield’s but with greater capacity for housing: over 420 sorely-needed units in Burlington’s core. At the end of October, another pittance of encouragement came: using $2.5 million in CARES grant money, Weinberger’s favored housing nonprofit, Anew Place, purchased the defunct Champlain Inn in Burlington’s South End, fulfilling the mayor’s 2017 promise of a year-round low-barrier homeless shelter.

History for once eschewing rhyme in favor of echo, Weinberger’s platform heading into the mayoral race for his fourth and ultimately final term was a medley of the same planks he’d run on the past three go-rounds, this time more dire and sullen: he would balance a once-again overdrawn budget; he would respond to a nuclear meltdown of the housing market by implementing developer-friendly policy; he would bring much-needed professional luster to the police force through pumping resources into it like there was no tomorrow. His challenger was Max Tracy, the well-liked and mild-mannered Progressive multi-term head of the Burlington City Council – for the first time in Miro’s political career a mayoral opponent with a Progressive party pedigree, a high local political profile, and the experience in city government to match.

Cocktail Hell is a nameless service industry professional in Vermont.