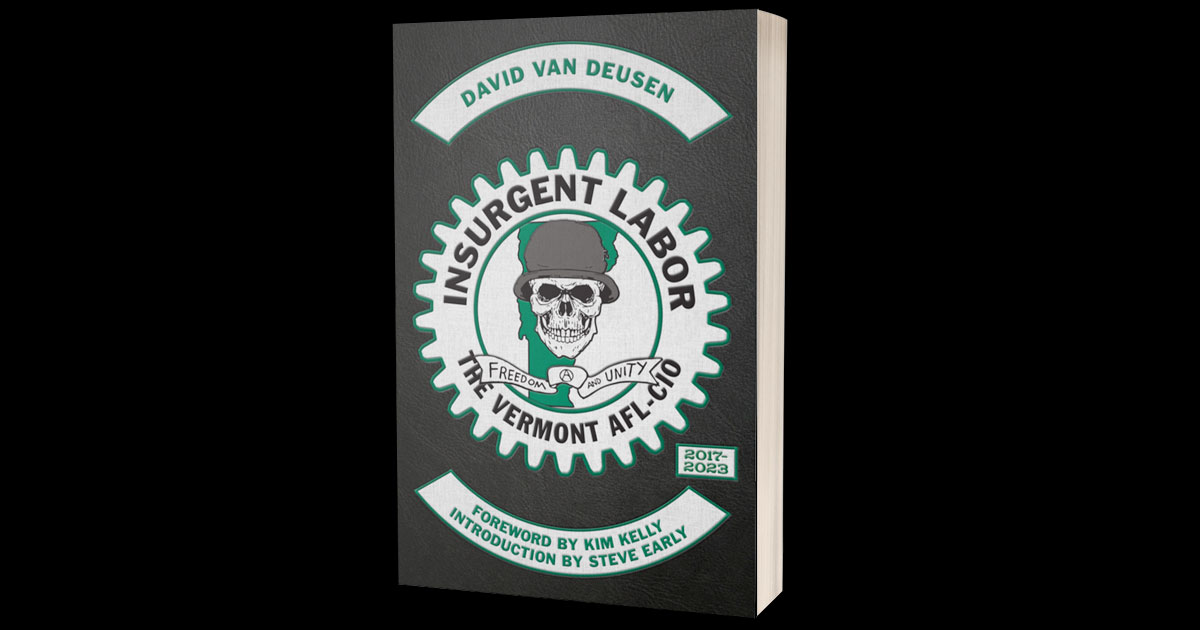

Published this summer by PM Press, Insurgent Labor: The Vermont AFL-CIO, 2017–2023 offers an inside account of what author David Van Deusen evidently saw as the beginning of an exciting new chapter in Vermont’s labor movement. A self-described libertarian socialist, he and allied reformers had taken over a sclerotic and increasingly irrelevant state labor council and doubled its membership, turning it into a bastion of working-class militancy.

The future looked bright, but the book proved an ill-timed victory lap. Less than a month after it went on sale, the insurgency appeared to have ended.

The losing candidate in the Vermont AFL-CIO’s 2023 election, a conservative from the building trades, had successfully appealed the results of that contest, and this August, he assumed the presidency. After a fruitless effort to persuade the AFL-CIO’s unfriendly national leadership not to force a revote on the basis of the LIUNA organizer’s procedural complaints, Van Deusen’s left-wing United! caucus folded, declining to put forward a candidate of its own. Even before the redo election, Van Deusen’s hand-picked executive director, Liz Medina, had resigned.

An AFSCME organizer, Van Deusen himself had stepped down a year earlier, after two proud terms as president, and had endorsed a successor, 31-year-old Katie Harris, a mental health worker from AFSCME Local 1674 and, like Van Deusen, a member of the Democratic Socialists of America. She had previously represented United! on a May Day trip to Havana, meeting the general secretary of the Federation of Cuban Workers.

Insurgent Labor’s afterword, penned last September after a fairly narrow victory for Harris, overflows with optimism. “Thus, it is with assurance that our progressive struggle will continue that I hand the reins of United! and the Vermont AFL-CIO to President Harris and the thousands of rank-and-file union members who will make even greater victories possible in the not-so-distant future,” Van Deusen writes.

What happened? The rise of United! generated rapturous coverage in the national left-wing media, but now, we’ve yet to see an autopsy report. A catalog of early triumphs, Insurgent Labor nevertheless suggests in some ways the fragility of what Van Deusen built in Vermont.

The book’s chronicles of close-call battles between Van Deusen and AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka show that the caucus faced long odds from the start. Before his death in 2021, Trumka opened dubious misconduct investigations and threatened to withhold funding or even to impose a trusteeship in Vermont. The hostility continued under his next-in-line, Liz Shuler, and United! partisans blame bias on the national level for the premature end of Van Deusen’s experiment.

Van Deusen foresaw such a possibility. In his book, he mentions the idea of establishing a “government in exile” in the event of takeover by Shuler, theorizing that, “given United!’s broad base of support among dozens of affiliated locals, we would be able to exercise leadership with or without the national AFL-CIO’s support and recognition.”

He may have overestimated his strength. The story of the Vermont AFL-CIO under Van Deusen has come instead to resemble that of the Nevada Democratic Party in 2021, when DSA members “rushed the cockpit” in a similar fashion, seizing control of an institution not as the culmination of a process of bottom-up political change but as a means to implement it from the top down.

But in Nevada, the outgoing leadership drained the party’s coffers before handing over the keys, and the insurgents floundered. Afterward, they couldn’t have written a memoir like Insurgent Labor, whose narrative brims with purposeful activity. Whether Van Deusen succeeded or failed in permanently transforming the Vermont AFL-CIO, he and his confederates didn’t sit around during their five years in power.

The book includes a blow-by-blow history of the campaign, the energetic organizing and strategic maneuvering that put the author and his allies into power in the first place. By crafting a confident and attractive reform program for an obviously moribund institution and using it to turn out sympathetic delegates from a wide variety of unions, Van Deusen helped boost attendance at the Vermont AFL-CIO’s previously desolate annual convention, and yearly participation at the event only grew after that.

In office, the new president set out to undo the federation’s reliance on “polite lobbying” in the statehouse and its habitual support for business-as-usual Democrats. Instead, he established ties with the Vermont Progressive Party, activist organizations, and social movements, and he used lobbying funds to hire labor organizers.

As a member of Champlain Valley DSA since moving to Burlington in 2021, I witnessed the second half of Van Deusen’s tenure. His Vermont AFL-CIO hired a few of our chapter’s young members (including our co-chair) as organizers, and for a period in 2023, I could hardly tell where DSA ended and the state labor council began. Together, we planned a big May Day rally at a park overlooking Lake Champlain, and we created a semimonthly program called Workers’ Circle, taking inspiration from a one-time training session led by Ellen David Friedman, the board chair of Labor Notes, in Barre.

Operating as a regular hourlong roundtable discussion where anyone who wanted to form a union or strengthen their existing union could drop in for advice from peers, Workers’ Circle helped the success of local organizing efforts among ice cream scoopers at Ben & Jerry’s and graduate students at the University of Vermont. Its casual, unscripted format and diversity of participants yielded remarkably wide-ranging and empowering conversations.

The Vermont AFL-CIO’s indefatigable executive director, Liz Medina, brought the pizza and often played the role of facilitator. I never saw Van Deusen, who, to be fair, didn’t live nearby. From what I heard, his vision – thankfully unrealized – was to turn the Workers’ Circles, which Medina had sought to expand from Burlington to Montpelier and Brattleboro, into official “central labor councils” of the AFL-CIO and to enlist them in his long-term fight to overhaul the national federation.

In general, Van Deusen had big goals. And ultimately, Insurgent Labor has little to say about the slow, human-scale work of cultivating shop-floor militancy: it seems to prefer the sensational grandeur of high-stakes politics. A major section, for instance, recounts the Vermont AFL-CIO’s decision in 2020 to authorize a general strike in the event of a “fascist coup” by Donald Trump following Joe Biden’s election as president.

Foreseeing armed conflict, Van Deusen simultaneously makes arrangements with allies in Quebec — legislators from left political party Québec Solidaire and friends from the labor union Confédération des Syndicats Nationaux — who prepare to shelter his young children across the border. Their father, though a likely “target of repression,” resolves to stay in Vermont and “defend democratic processes” with possible help from “a loaded .357 Smith & Wesson revolver” and “a twelve-gauge laid across the back seat of my Jeep.”

Adding to the dramatic tension, Trumka accuses Van Deusen of overstepping his authority in calling for a potential general strike in the Green Mountains. Facing intimidation, Van Deusen goes to the press, where publications like In These Times and CounterPunch – not to mention economist Richard D. Wolff’s podcast – rise to his defense. So do various nationally prominent activists, who sign an open letter praising the Vermont AFL-CIO.

In terms of public relations, United! always had remarkable success. The admiration of out-of-state journalists couldn’t save it in the end, but Van Deusen’s popular image as a gun-toting, whiskey-drinking, Harley-riding backwoodsman allowed progressive media to see him as an authentic leader of salt-of-the-earth Vermonters even as his political hobbyhorses occasionally seemed to belong more to the academic left.

During United!’s reign, the Vermont AFL-CIO printed countless copies of its new “Ten-Point Program for Union Power,” also known as The Little Green Book. The pocket-sized publication contains not just the eponymous program but ten other official statements and policies from the federation. These include one dedicated to Cuba, one to Palestine, and two to Rojava.

Despite Van Deusen’s best efforts, the average worker in Vermont probably still doesn’t know much about the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria. But while it lasted, enthusiastic onlookers like me enjoyed believing, as much as we could, that a radical, anticapitalist, internationalist labor movement really had emerged in our state.

As objects of mostly symbolic support from the Vermont AFL-CIO, Cuba, Palestine, and Rojava all appear again in Insurgent Labor, alongside a discussion of Black Lives Matter and the state labor council’s controversial 2020 moratorium on organizing new police unions (in spite of the existing police officers among its affiliates). But high-profile political gestures make up only one part of Van Deusen’s story, which also contains detailed accounts of campaigns to win “responsible contractor” ordinances in municipalities and to defend public pensions, amid other less flashy subjects.

Unfortunately, the author’s relentlessly boastful tone makes the eventful text feel a bit monotonous. But that’s not to say that Van Deusen has nothing to boast about.

For example, his unconventional legislative strategy paid off earlier this year when, without a professional lobbyist in Montpelier, the Vermont AFL-CIO used grassroots momentum to pass public-sector card check and a ban on captive audience meetings on the state level. United! made headlines for good reason, and its break with the business unionism of the past was real and necessary.

“One fact that I discovered, when I brought up the need to build the Vermont AFL-CIO, was that a majority of members had no idea what the AFL-CIO was,” Van Deusen explains. “The state labor council was so far removed from their day-to-day reality that they did not even recognize the name.”

Van Deusen made progress in boosting rank-and-file involvement, but today, does an actual majority of the 20,000 members of the Vermont AFL-CIO’s affiliated unions know anything about the state labor council or what it does? It’s hard to imagine.

Last year, the Vermont State Employees Association – a “reactionary” and “risk-averse” union by Van Deusen’s description in the book – became an affiliate, and its membership now makes up 30% of the Vermont AFL-CIO, so the next generation of reformers will face an uphill battle. With help from the Vermont IWW, Champlain Valley DSA still runs the Workers’ Circle in Burlington, but now we have to buy the pizza ourselves.

Brett Yates is a member of the Champlain Valley Democratic Socialists of America. He lives in Burlington, Vermont.