Mayor Emma Mulvaney-Stanak announced on November 19 that Burlington Police Chief Jon Murad will not be seeking reappointment in June 2025. Murad, who has led the Burlington Police Department since June 2020, plans to remain chief until April as a search for his replacement gets underway.

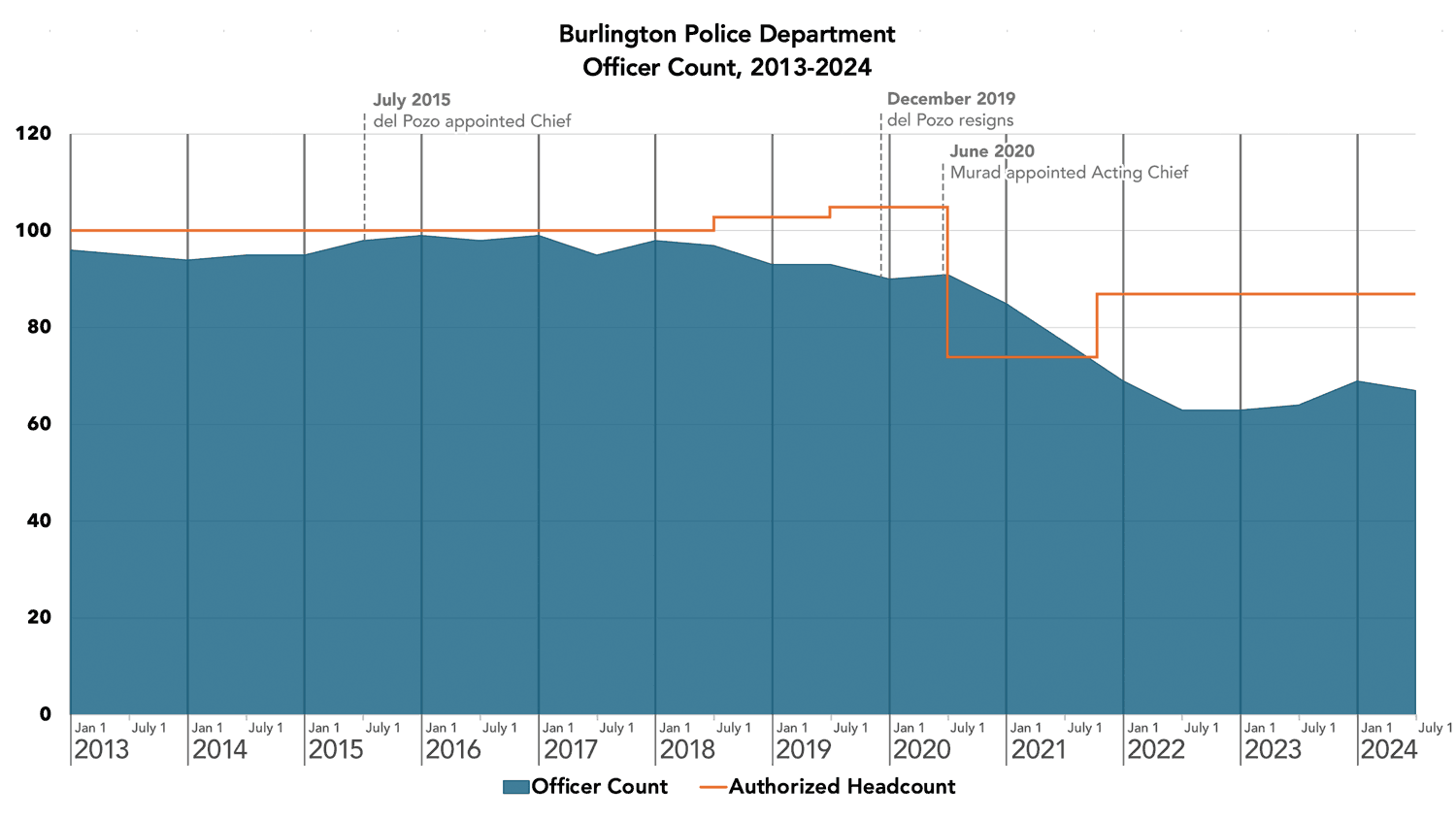

In a December 5 report to Burlington City Council, Chief Murad underlined a narrative that he has recounted at every opportunity for the past four years: the cause of all the police department’s woes can be traced to a single city council vote in 2020 that reduced the cap on total sworn officers, through attrition, from 105 to 74.

Burlington has for years been known in the national media as the city that “defunded the police” in the wake of the George Floyd uprising. But what do the numbers say? And what factors drove the department to its current state?

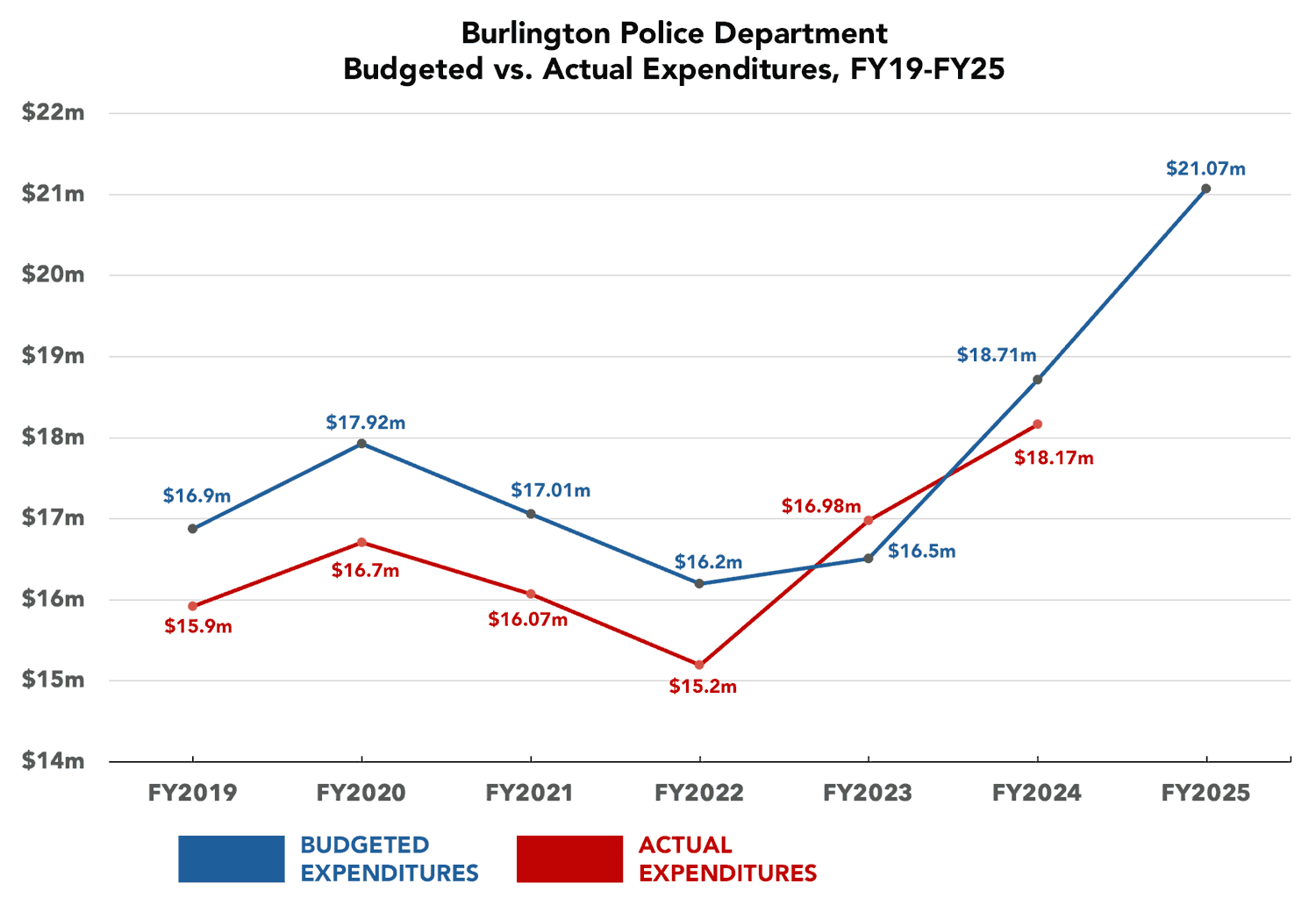

Police Budgets Have Always Been Higher Than the Prior Year’s Expenditures

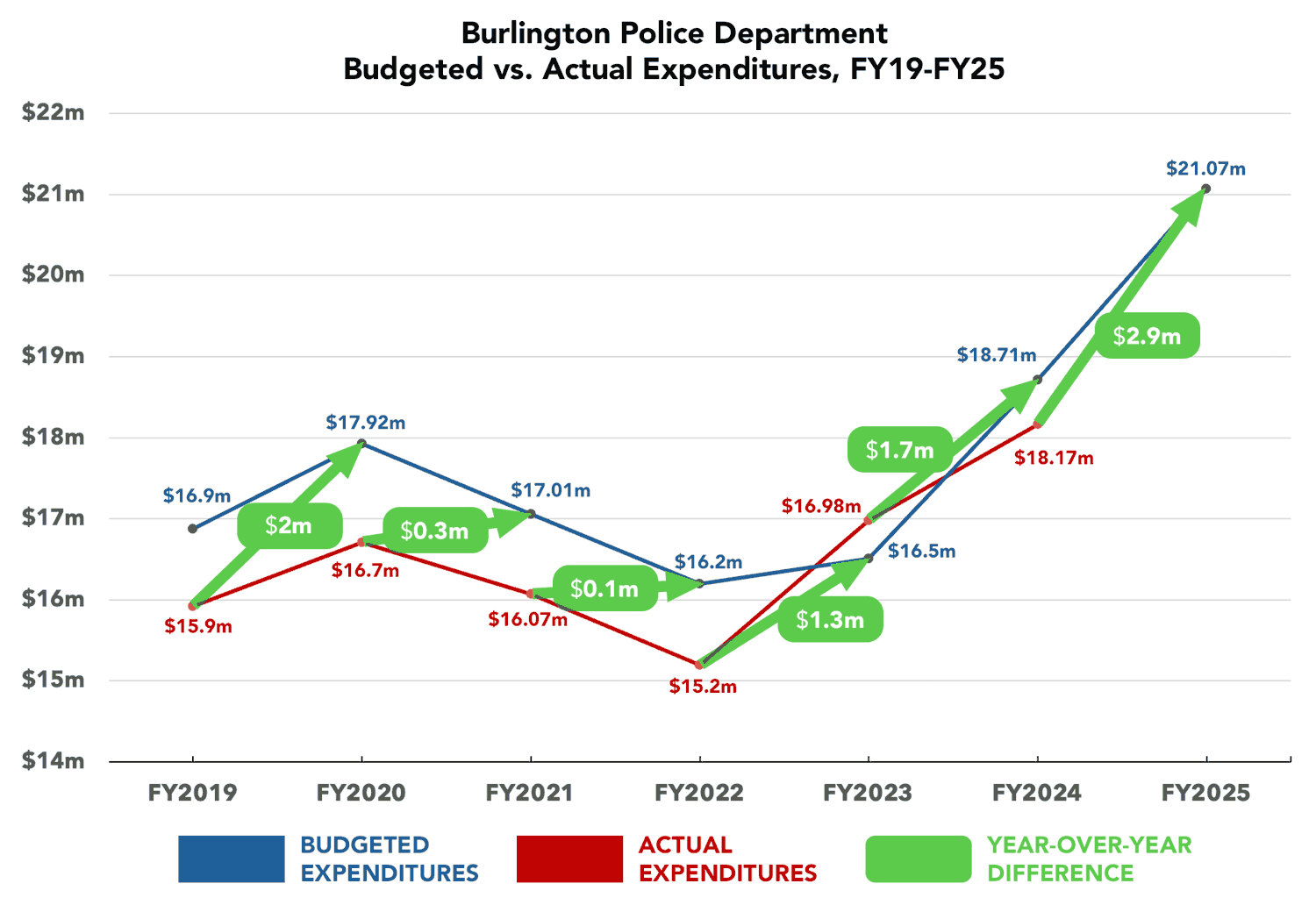

With one exception, Burlington Police Department expenditures have consistently been well under what has been budgeted for it. From FY2019 through FY2024, we can see that the department left a total of $4.2 million on the table in unspent funds. (Fiscal years begin in July the year before: for example, fiscal year 2020 started on July 1, 2019. Original, not amended, budgets are being used in this analysis.)

Even in years when the department’s approved budget decreased, the budget total remained above the previous year’s expenditures.

This includes the particularly contentious FY2021 budget, passed in June 2020. Both then-Mayor Weinberger, a Democrat, and Burlington City Council, which had a de facto Progressive majority, floated the idea of trimming roughly one million dollars from the proposed police department budget in response to overwhelming public pressure — but the end result still managed to be hundreds of thousands of dollars above what the department spent the previous fiscal year.

Far from defunding, Burlington has never failed to give its police more money than it had spent.

Burlington’s current budget, fiscal year 2025, passed in June, the first budget passed under Emma Mulvaney-Stanak’s mayoralty. It was a painful one. Mulvaney-Stanak inherited a $14.2 million deficit from Miro Weinberger, her predecessor. To close that deficit, the city had to use one-time funds, raise taxes, and order city departments to find savings and leave vacant staff positions unfilled.

The police department, however, was one of the very few exempt from such belt-tightening.

Burlington’s present police budget is a bigger actual-to-budgeted increase in police funding, $2.9 million, than any under Weinberger’s twelve-year tenure. It is likely the largest increase of its kind in the city’s history.

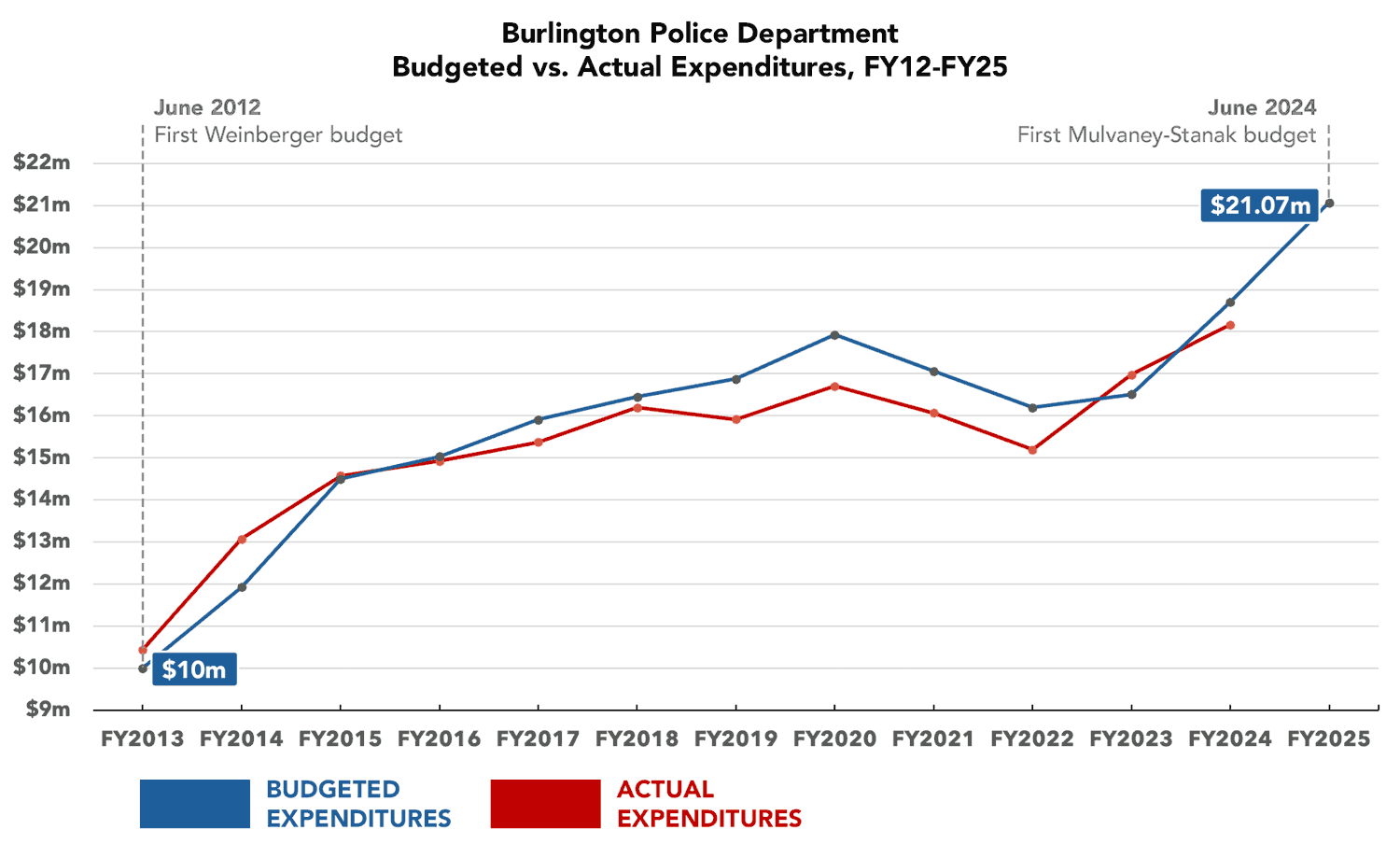

The present police department budget is more than double Weinberger’s first budget, fiscal year 2013. To put the current budget in perspective: since 2012, the police budget has increased by 111%, while cumulative inflation has been 37%. At the same time, the city’s population has increased by roughly 5%. Comparing annual reports for 2012 and 2023 (the most recent available), the number of annual total police incidents has slightly decreased.

The current budget also contains, unofficially, a blank check provision: Mayor Mulvaney-Stanak has pledged that should the department be in a position to grow the total number of officers beyond the additional ten for which it is budgeted, the city would “find the money” somewhere, despite the historically tight fiscal situation.

Burlington Police Issues Long Predate 2020

The vast majority of Burlington Police Department’s budget is spent on salary and benefits. The department’s persistent failure to retain and recruit the number of employees for which it is budgeted goes a long way to explain the significant gap shown in the charts above.

While much hay has been made about the employment effects of the FY2021 budget season, which included a reduced cap on total officers to be met by attrition, the officer count decline was already noticeable by early 2019 — despite the officer cap being raised to 103 and then to 105.

Recruitment and Retention is Not Just a Local Problem

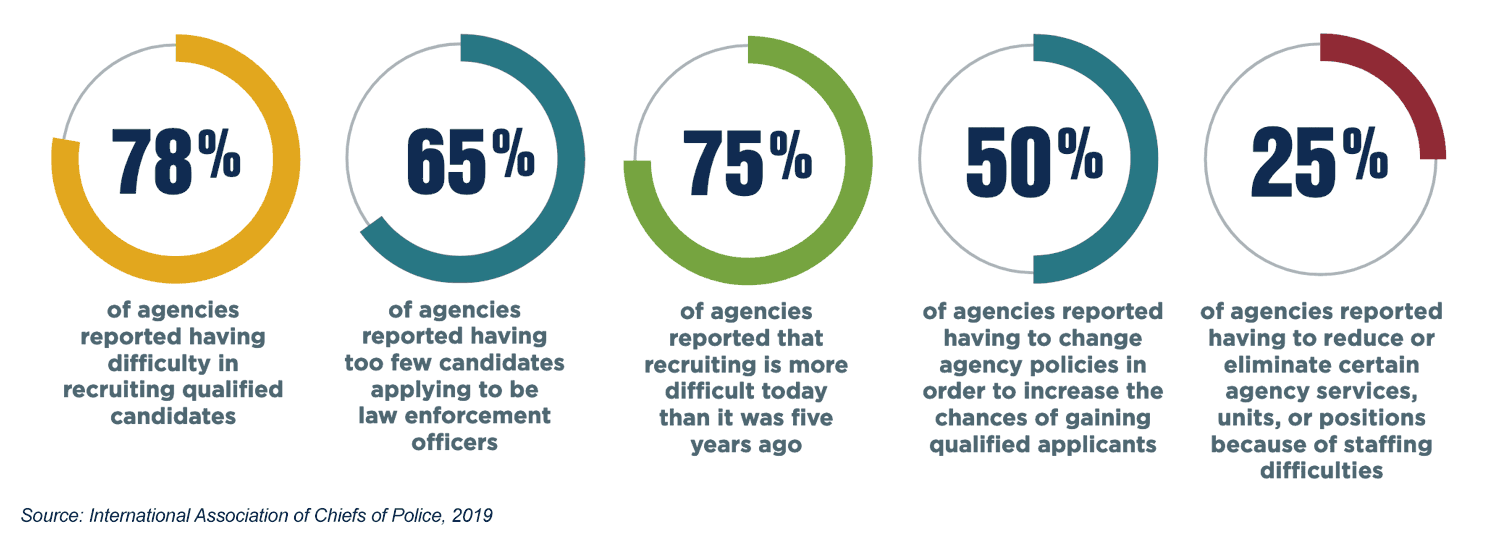

Burlington isn’t alone in its recruitment problems. Even before COVID-19 hit, 2019 report by the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) found an ongoing, widespread officer recruiting crisis.

The report cautions against assigning blame to a single factor: “The IACP survey on recruitment demonstrates that the difficulty in recruiting law enforcement officers and employees is not due to one particular cause. Rather, multiple social, political, and economic forces are all simultaneously at play in shaping the current state of recruitment and retention.”

A 2023 analysis by the Marshall Project found that police departments are not alone in their hiring woes since the pandemic began: such challenges continue to face all public sector jobs, from sanitation workers and bus drivers to firefighters and paramedics, as many workers chose retirement or simply reevaluated their work-life balance in the light of COVID-19:

Tulsa Police Officer Mark Ohnesorge said he understands why some people believe that anti-police talk has driven officers out of the profession. But as the person in charge of recruiting for the department, he said he almost never hears those concerns from people who decide against law enforcement careers.

Instead, Ohnesorge and experts said, police departments are losing officers to jobs in the private sector, which offer both more money and more flexibility.

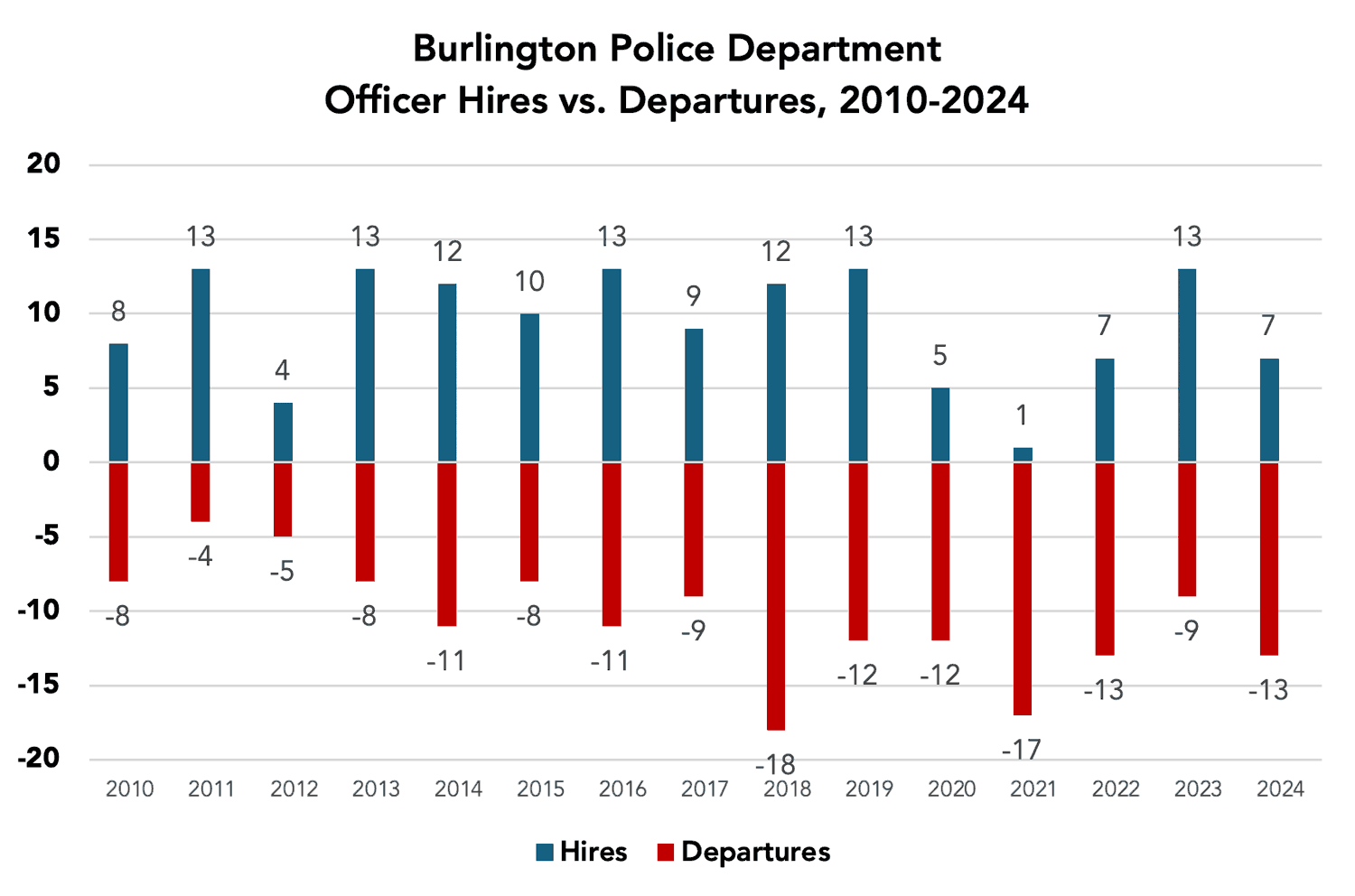

As department data shows, the problem of officer turnover in BPD long predated June 2020.

Retirements are the easiest for police departments to plan for, as they tend to cluster around the time it takes for officer pensions to vest. Burlington has faced two waves of retiring officers, first in 2017-2018 and then in 2021.

BPD departures began outpacing new hires in 2018. In an interview in November 2018, shortly after he was hired as Deputy Chief of Operations, Murad noted the difficulties of recruitment: “He said like many departments across the country, recruitment of qualified officers poses a challenge,” VTDigger reported. By June 2019, then-Police Chief Brandon del Pozo remarked to the city council that there was an increasing trend of officer departures, with retirements being the single biggest factor.

The second wave of retirements hit in 2021. In a December 2020 presentation to Burlington City Council, Chief Murad warned that there would be twelve additional officers eligible for retirement by September 2021. In 2021, eight of the seventeen officers who left retired, the largest annual number of retirements in over a decade and more than the previous three years combined. Were it not for those retirements, the department would have faced a lower than average number of departures that year.

Sidenote: Are BPD’s own numbers reliable?

These potential retirement waves were, or at least should have been, known to department and city leaders for years. However, Rake examinations of BPD reports suggest the department has a somewhat loose grasp of its own employment figures.

For example, take the number of officers that BPD hired in 2015, a number that should be well settled by this point. Murad’s December 5, 2024 report lists it as 10. Murad’s earlier report on February 23, 2024, however, lists it as 9. And Murad’s May 31, 2022 report lists it at 8. In a similar fashion, the total officer hires in 2017, 2018, and 2019 were each increased by one with no explanation given.

The net result of these changes is a rosier picture of pre-2020 recruitment numbers.

We use the department’s most recently reported numbers for all our charts, but we take them with a grain of salt. We encourage our readers, and policymakers, to do so as well.

Chaos Among the Top Brass

In the years leading up to the pandemic, Burlington Police Department found itself stumbling over problems of its own making.

In 2018, police actions in three separate incidents resulted in officers Jason Bellavance, Cory Campbell, and Joseph Corrow facing excessive force lawsuits, which would take years to settle at significant city expense.

It is well understood that officer morale and the overall culture of policing in a department “comes from the top.” Amid that cloud of ongoing lawsuits, at a time when city officials expected a steady hand from the chief and deputy chiefs to both navigate the crisis and change the internal culture and practices of the officers, Burlington police leadership embarked on a truly remarkable series of unforced errors.

At one point, Burlington had four police chiefs over a six-month period.

A brief recap:

- Police Chief del Pozo resigned in December 2019 for having harassed a prominent critic (and Rake editor) using an anonymous Twitter account.

- Mayor Weinberger appointed Deputy Police Chief Jan Wright to replace del Pozo.

- Weinberger demoted Wright back to deputy chief less than seven hours later, when it emerged that she too had used a fake social media account to argue with critics on Facebook.

- Later that week, Weinberger appointed Jennifer Morrison, former chief of the Colchester Police Department, as an interim chief until a search for a permanent chief could be concluded. Morrison assumed her office in January.

- Deputy Chief Wright resigned from the department entirely in February, following the discovery of a second fake social media account she had used.

- In April, Weinberger announced a one-year pause in the police chief search process.

- Morrison remained Interim Chief until June, at which point she took leave to support her husband through a medical procedure.

- Deputy Chief Murad was tapped to be Acting Chief during Morrison’s absence.

- In September, Morrison resigned instead of returning from leave, complaining about what she saw as Burlington City Council’s “social activism” and “mismanagement.”

- Chief Murad has led the department since then.

Murad’s planned departure by April is part of a larger leadership exodus in BPD. Deputy Chief Wade Labrecque retired in September, and Brian LaBarge, BPD’s other deputy chief, is expected to retire in July. This means that the Burlington Police Department will find all three of its top positions empty in 2025.

Self-imposed Recruitment Woes

Members of the police commission — and general public — have long noted that it is difficult to find job openings for BPD officers in the expected places. On the City of Burlington’s LinkedIn page, there are no job listings. There are frequent posts that mention open positions, but the lack of formal listings means that applicants using LinkedIn’s job search will never notice Burlington’s openings. In November, the city announced it would no longer be posting to another popular job site, governmentjobs.com, instead hosting them solely on the city’s own webpages.

In a July 18th Public Safety Commission meeting, Corporal Carolynne Erwin, the department’s Recruitment Officer, expressed exasperation over how few job applications they have been receiving. Erwin described the hiring landscape as much different than the last time she was doing recruitment for BPD years ago. She said that in 2010, the department would receive 300-350 officer job applications in a year, a stark contrast to what the department gets now. As of July, “we’ve received 26 applications so far,” she said. “Last year’s number, I think I saw, we had 112, so this trajectory is insanely low.”

As applications fell, expectations of applicants did, too.

“I think I’d say prior, back in the 2010 era, like, if your paperwork wasn’t filled out correctly, you wouldn’t get through very far, because attention to detail is so important for officers,” Erwin said. “If you didn’t show up for a PT [physical training] test, and even let me know, we’d probably be like, ‘oh, you’re done. You didn’t show up for an appointment.’ Now it’s this different era too, where I was like, ‘oh, you didn’t show up, it cost us $450, [but] I’ll still schedule you for another one, because you already made it this far.’” She noted that they had reduced the fitness requirements for new officers. “I also have a lot of people not passing the run, and our PT standards used to be crazy harder, and right now I’m struggling with people,” Erwin said. At one point, Erwin even called an applicant’s mother to try and reach him after he had stopped responding.

One culprit for reduced applications is the changing nature of the job market. Hiring outreach now overwhelmingly takes place on digital and social channels, beyond the classifieds and centralized job sites of the past. “I mean, really, I just really don’t know what to do… I don’t even have, like, LinkedIn, Facebook. That’s not my forte,” Erwin said.

Meanwhile, the department apparently lost access to its Instagram account back in late 2018. It was only able to resolve this problem in July of this year, not by recovering the password, but by simply creating a new account.

BPD placed an ad in the March 8, 2024 edition of the New York Post. A slide touting this fact has been in most monthly report to the police commission since, at times the only substantive recruitment update offered. By the department’s own reckoning, it resulted in just one visit by a prospective applicant.

Recruitment Coordinator Anhad Bajwa resigned in October to move out of state with her family. No replacement has been hired yet.

Officers are Miserable

Earlier this month, VTDigger obtained and published an internal officer survey conducted by the police union, the Burlington Police Officers’ Association, over the summer. The topline number: roughly 75% of officers reported morale was “poor” or “terrible.”

The internal survey is an opportunity to see the opinions of officers when they are talking to each other, not speaking to the public or elected officials.

Despite a constant outward-facing drumbeat from department leadership and the officer union blaming city hall for their problems, members ranked both the mayor and city council relatively low among their concerns. The overwhelming majority of suggestions to raise morale were variations on familiar themes: increased staffing, pay, working conditions, and benefits.

The responses are a sign of the classic downward spiral effect that can happen in workplaces in every sector: fewer staff end up doing more work, which increases stress and lowers job satisfaction, which leads to even fewer staff. Several respondents stated they were looking to retire or actively searching for a job elsewhere. Officers also directed their ire toward their supervisors and top management within the department.

Of course, anger at city hall has remained. The 2020 officer cap vote appears to have taken on mythic proportions among some officers, a kind of original sin that only deepens with the passage of time and on which all present and future problems are blamed. One officer survey comment complained of “no support from the city council, mayor or the people.” In a WCAX podcast just two weeks ago, a BPD detective made the astonishing claim that the city in 2020 “fully defunded us.”

Despite the city raising the officer cap three years ago, ballooning the department’s budget, voting to pour more money into bonuses for retention and recruitment, and approving a generous collective bargaining agreement in 2022, officers’ minds remain fixed on what they perceive as a singular betrayal, unmoved by any events since.

An expected result of publicly pronouncing themselves perennial victims under attack is that the solution to their most pressing problems — being overworked and understaffed — becomes more difficult, as some potential recruits have aimed for other, quieter, departments. The Rake reported last year a similar self-defeating dynamic among Burlington’s retailers: years of apocalyptic language they conveyed to the media over an uptick in public drug use and unhoused people in the Church Street area resulted in a predictable reduction in local foot traffic and a general impression by out-of-towners that Burlington was unsafe and to be avoided entirely.

The Burlington Police Department Has Done More to Defund and Dismantle Itself than Abolitionists Could Have Hoped

Waves of foreseeable retirements. Excessive force by officers. Incompetence and high turnover in management. A confluence of problems of its own making meant the Burlington Police Department placed itself in a perilous position even before the crises of 2020 began to unfold.

Officers, from the beat cops to the top brass, have managed to undermine their own institution in ways that no protest at the height of the George Floyd uprisings could have done.

The Burlington Police Department, having tied its shoelaces together, blames everyone but itself for its careening and flailing about. The permanent, structural allies of the police — local politicians, landlords, and business owners — have done their best to shore up and echo BPD’s damage control talking points. During this year’s mayoral campaign, there was precious little daylight between Joan Shannon’s and Emma Mulvaney-Stanak’s rhetoric on the centrality and importance of increasing resources and support for the police. Local news outlets, especially broadcast media, managed to paint the largest municipal police force in the state, well-armed and well-paid, whose members can threaten terrific violence on Burlingtonians, as a cowed, beleaguered, and impoverished group ground down by an ungrateful public and political class.

The Burlington Police Department’s incredible success in shaping the political narrative — one of the few successes the department can point to over the past five years — becomes more understandable when one recalls Chief Murad’s career prior to his tenure in Burlington. Murad worked closely under New York Police Department Chief Bill Bratton in the wake of one of their officers killing Eric Garner and the widespread outrage that resulted. He was tapped not to spearhead long-needed reforms of police culture and practice, but instead to build out the department’s news and media outreach strategy to shore up NYPD’s public image.

As Mayor Mulvaney-Stanak leads the search for Chief Murad’s successor and prepares to negotiate the next police union contract, the department is doubling down on its worst impulses. For them, bigger budgets aren’t enough. Signing and retention bonuses aren’t enough. They want contrition. Penance. In his December 5 report, Murad said the city should “make a formal apology for and repudiation of” the 2020 hiring cap, yet another gesture in a long line of gestures to placate what appears to be a department of permanently embittered officers.

The city’s purse strings may be held by city council, but the decision whether to put up with this police department, riven with dysfunction and unable to meet even its own modest goals for the better part of a decade, is ultimately up to the people of Burlington.

Patrick is a writer and organizer based in northern Vermont. He is on the editorial collective for The Rake Vermont.